I love murder drones. I think they’re such great little guys. Bring me a robot maid and I am yours forever, etc. But watching through the series itself actually took me a few stabs, and I think it’s due to a few design decisions that make following the plot unintuitive and add some friction to what’s otherwise a very fun show. So I want to talk a little bit about that friction, even though the entire thing is still a good time overall.

Indie Animation

First, the obviously relevant context is that Murder Drones is made by Glitch, which is a small independent animation studio. And independent animation necessarily comes with constraints. It’s incredibly exciting that we have the technology for small teams to make work with this quality and scale, and I don’t at all want to take that for granted. But I think a lot of the friction I have to talk about comes from fundamental trade-offs that come from that setup.

Since their resources are very limited and good animation is expensive work, there’s a pressure for everything to be compressed. Short episodes with short shots in an eight-episode miniseries mean the project is feasible, but it’s hard to get all your fun ideas in while still sufficiently paving the way for them to land properly.

Structurally, a small indie team also carries the risk of skill gaps. I don’t mean to make any criticisms of anyone in particular on the project here, but this kind of team might not necessarily have experienced television writers or producers. And, with a small independent team, there might not be enough of a test audience to catch things that could be improved, or not enough budget to re-iterate for minor improvements. So those are all categories of things that can easily run into trouble.

Independent serialized animation like this is a relatively new phenomenon, but these are going to be the same sorts of challenges projects like RWBY and Helluva Boss have. (Although I think Murder Drones is significantly better than both of those.) So while there are common environmental factors that can make this kind of project a little extra rough, the way that roughness actually manifests is interesting.

It’s not glaringly bad

The reason I’m interested in talking about this at all is that I noticed the friction as part of my own experience, but it wasn’t linked to any obvious problems. In fact, the whole reason I’m writing this is Murder Drones felt like it should be great, and I was surprised there were things that still weren’t quite clicking. In re-watching the series to write this, slowing down and zooming in to catch every piece made the effect much harder to see. It’s hard to put my finger on exactly what caused the effect. Which is why I want to! The dynamics you can barely see are always the most interesting to understand.

This is one of the reasons I really like understanding rules and best practices, because when you’re zoomed-in working on something, it can be easy to miss subtle things about the way the work comes across. Something can seem good as you’re studying it but still have a problem. And when you can’t see the problem directly, you can work it from the other direction.

Things that are fine

There are a lot of obvious things about the show that might seem like evidence of “low-quality” internet media, but I actually don’t object to any of those.

You can feel, in its construction, an intent to appeal to modern fandom culture. It’s like… you know the Hasbro shows like G.I. Joe that were mostly designed to market toys? It’s like a non-evil version of that. Instead of trying to sell you products, the show baits you to engage with the show. There are so many fun characters, and there are lots of great outfits to put them in. And you gotta make a drone ‘sona.

It’s all very shippy. It has so many characters who are incredibly cute together, and it’s just begging you to draw fanart of your faves kissing. There’s a big climactic resolution where the two love interests cement themselves as a ship, and they live happy, harmonious lives in a good* ending.

Like, in the third episode, right after a dramatic wedge is driven between them Uzi and N take each other to prom, complete with a dress and a tuxedo. And then this fight happens.

show knows what it’s about

And with all that set up, I feel like I’m poised to really tear down the show with some really biting cynicism, but that isn’t my point at all. I’m guessing there’s some hate for the show from people who subliminally feel pandered to by all that, but I actually think it’s fine.

It’s not a sin to understand and cater to the specific media environment you know you’re operating in. One might argue that’s part of making a good show. I think it’s easy to take the odd vibes the show prompts and pair those to this sort of fandom cynicism the show also prompts, except I repeat I don’t think the fandomism is the problem.

As a show, it really intentionally embraces the edgy random mid-2000s teen vibe, and I’m not holding that against it. It gives the show some fun character. The whole show is really kind of a love letter not just to fandom, but that particular cringy dorky teenager version fandomhood. Which is just a fun angle to take teen characters and run with!

The silly background humor is fine, the homages are fine, poking fun at tropes is fine too. (Although the humor in the pilot is particularly weak, unfortunately.) There is definitely a “cringe” flavor in the background, but I don’t think that actually hurts it.

And before I get into what does hurt it, I have to list off a few more ways the whole show is genuinely excellent:

- Character design

- Species design

- great looking animation, lighting, textures

- A lot of stuff is glowy but it’s the right kind/amount of glowy

- faces are great

- Thanks Unreal Engine 5

- Consistently sick as hell AS effects

- good lord

- Solid voice acting

- Good performances

- Characters felt right

- Never took me out of the moment

- Soundtrack!

- Just the right combination of fitting and memorable

- but not overbearing even in an already crowded show

- it’s got The Juice

Confusion and signaling

No, I think the core problem is confusion. Not any one confusing decision, but a cumulative effect from many tiny things that don’t communicate information well to the viewer. The overall effect is that the plot is hard to follow, and so despite its good qualities, the show is more difficult to watch as a story than it needs to be.

The show makes it unnecessarily difficult for a new viewer’s to intuit a mental model of the story, the world and its characters. Several factors interfere with the story’s ability to communicate, and so people have a hard time forming an understanding of both the mechanics of the world (powers, technology, setting, and elements of the mystery) and the characters themselves (histories, relationships, motivations). Many small factors add up and confuse the plot, creating a narrative situation where a fact can be telegraphed to the viewer without them knowing what that is supposed to mean.

After watching through the series I’m not still confused by the plot, so I don’t think it’s “confusing” in retrospect. The problem is the interaction it has with people trying to watch through the series for the first time, without knowledge from later episodes. And Murder Drones being a finished series is a relatively new phenomenon, so for a long time, that group included everyone.

I think my first reaction at the top of the article about loving the little guys is a common reaction of the show as a whole. Fans of murder drones seem to be fans of the characters first and foremost.

So the answer to “what’s wrong?” is “a lot of nitpicky technical things”. Most of these aren’t even mistakes or errors per se. The pieces aren’t objectively wrong, they just have the wrong effect when put together. And I have no particular film training that would let me talk precisely about these little mechanical things! But I’m going to try anyway.

Also, I’m not Cinemasins, and I’m not here to list “plot holes”. That’s not the problem I care about here. There’s a scene in the pilot episode where one robot fires an EMP blast at another robot, and only her target was hurt. And it’s fine. It was part of a fight scene, it obviously read as a direct attack, and it feels narratively consistent for a hit to the target to only hurt them. A story doesn’t have to be perfectly realistic; what matters is the experience, which requires that it be effectively communicated to the audience.

Why am I writing about all the parts I don’t like if I think the show is fun and you should watch it? Because I already spent all this time asking myself what was bugging me and painstakingly figuring out the answer. And maybe I just wanted an excuse to take a whole bunch of pictures of them. Criticism is my love language. I’m so sorry.

Visual

Everything is gray

The show is set on an exoplanet where the atmosphere has been destroyed, leaving the planet in a permanent winter only robots can inhabit. Originally this was a mining planet set up as a utilitarian space, and most interiors are industrial spacer bunkers built with utilitarian industrial lighting. The problem is when your main locations are space-y metal interiors lit by cold fluorescent light and cold gray outdoor snowscapes, everything is just a foggy blue-gray, all the time, indoors and outdoors.

Weather: gray

Weather: gray

It’s gray inside too. These are all different locations

This one’s a rustic wooden cabin

This is kind of the opposite of a visual language. Instead of using visual cues to give the viewer more information and signal a contrast between different locations as shots change, the lighting/design almost obscures information about the environment, and even obfuscates some scene transitions.

There are some fun exceptions to this, like the human-inhabited areas that get incandescent lighting, as opposed to cold industrial light. Uzi is consistently color-coded purple, and Doll gets this interesting orange-red. Episode 3 gives characters’ personal rooms this very vibrant color coding that I think works really well.

Bad early character recognizability

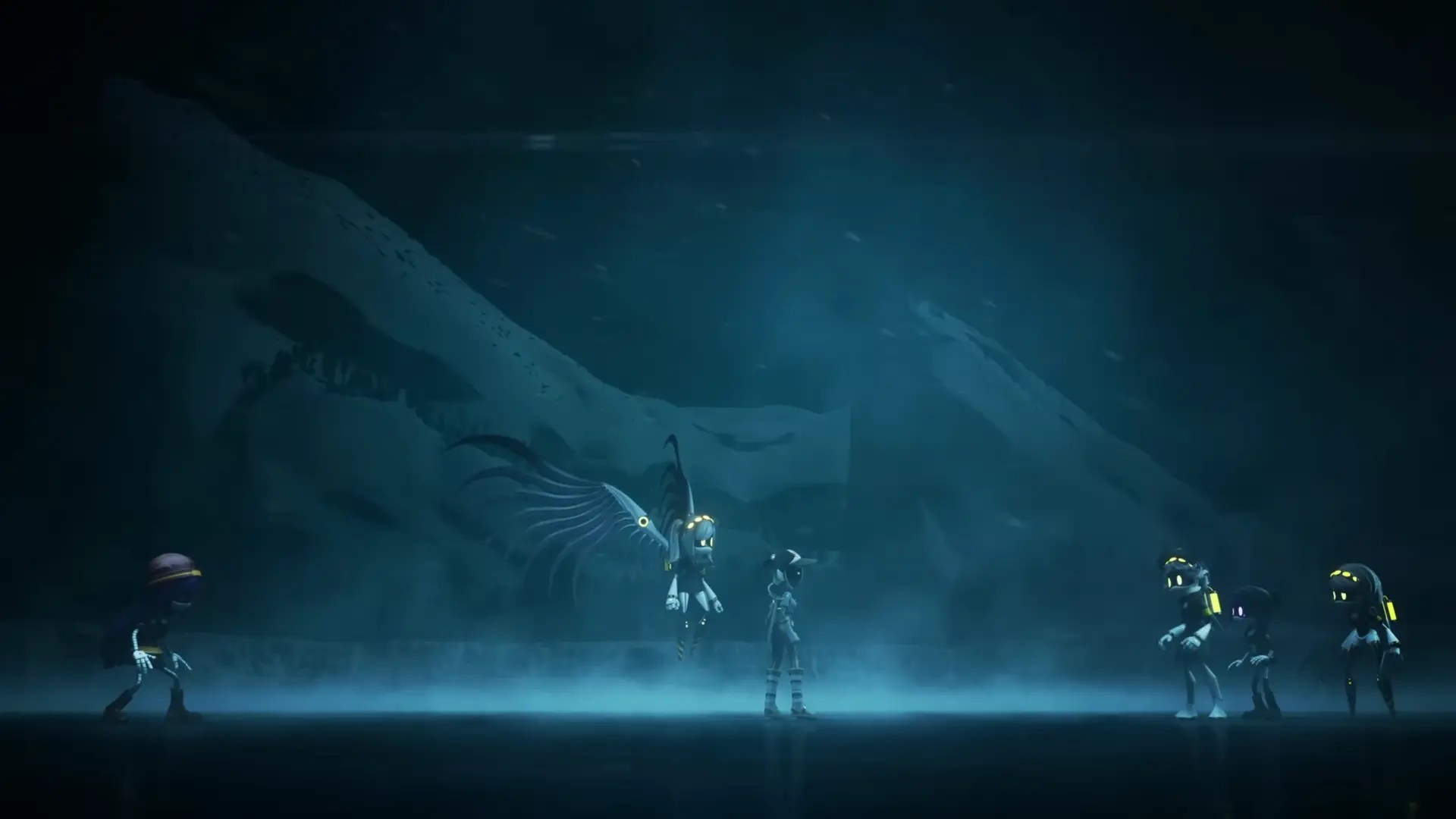

Not everybody, just the four disassembly drones.

All the disassembly drones share the same white/black/yellow/hazard color scheme, the same hair color, the same wings, the same tail, the same silhouette (sans J), and the same set of facial expressions. When they’re engaged in combat, they switch to an alternate combat form which is the same for all three of them with no distinctions. We’re introduced to three of these characters at once.

The color scheme issue alone is a killer, but all three drones sharing most of the same secondary and even tertiary characteristics is murder for readability.

This is most impactful in the pilot, because that’s when viewers are first introduced to the characters, and also when there are the most disassembly drones around at once. And it doesn’t help that V and J have the same basic alignment and narrative relationship to N and Uzi. Or that the serial designation letter names “N”, “V”, and “J” trigger the foreign name effect. It helps a lot that they get rid of J for most of the series.

But even after the pilot, this does keep coming up. Especially when a figure is obscured, it can be genuinely unclear who’s who.

generic disassembly drone or someone we know personally? it matters!

generic disassembly drone or someone we know personally? it matters!

Weirdly, even though they’re much less important to recognize, the relatively unimportant worker drones have much more recognizable distinct characteristics. And not by a small margin! They have actual designs complete with color schemes!

even if most of their designs came free with their archetype

Similarity in general

This issue of things being similar to each other in unhelpful ways keeps coming up. Sometimes two things are vaguely similar and it turns out they’re supposed to be deeply connected, and sometimes things are extremely similar but totally unrelated to each other.

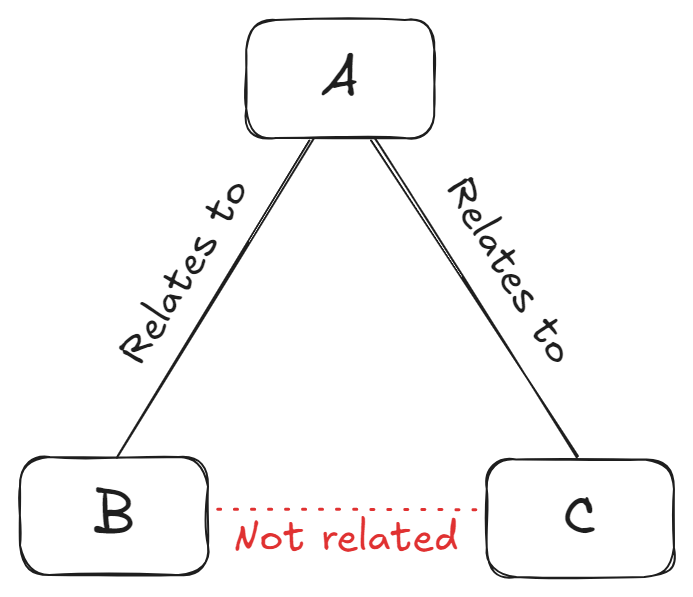

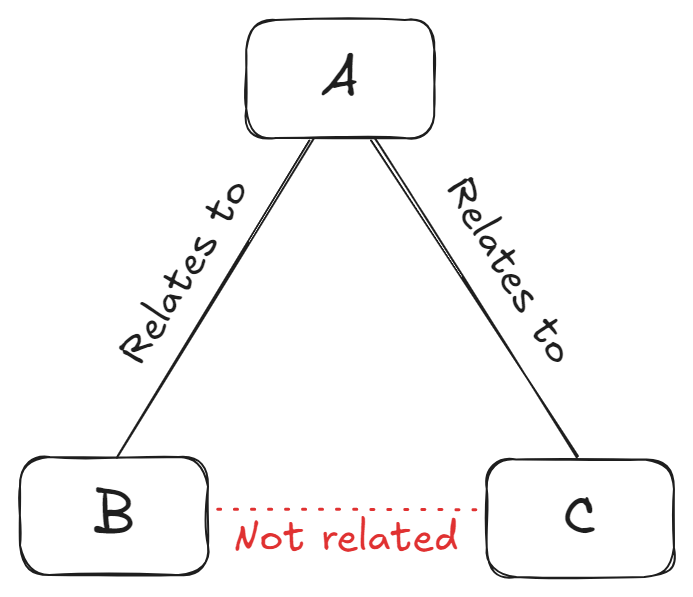

This creates a little conceptual problem. I called this Bad Triangle as a placeholder name, and I can’t think of anything better, so I present to you the Bad Triangle:

Concept A is introduced, and then it’s revealed that it has the same relationship to B as it does to C. This is classic Writing: if a parallel structure is set up like this, it should be to communicate that B and C have a sibling-like relationship. But if they don’t, then the viewer can’t reliably make connections and can’t form a clear understanding of the puzzle. Many of the communication issues I’ll point out are Bad Triangle Problems.

This isn’t limited to strictly visual similarity. Episode 2 and episode 3 both start with scenes where a lone worker drone inside their bunker is singled out in the dark and murdered by a supernatural force. These events are completely unrelated. They’re done by two different murderers using two different methods for two different motivations. They don’t even know the other one happened. Thematically, these events are utterly unrelated, but the viewer is signaled to think they’re parallel, since they’re presented in the same way in quick succession.

We’re shown a design of cute little robot bugs in episode 3 as a symbol of death and decay, but then that same model and design is reused for a sentient helper robot. And it’s still a bug they pick off the ground. Two very different roles for the same thing, presented in such quick succession there’s no indication which one is the anomaly in this world.

As another quick example, Uzi’s organic bat tail has a distinctive design that is noticeably identical to JCJ sentinels, even though they’re totally unconnected.

But, at the same time, you’re supposed to be able to intuit that these are just two variants of the same thing, only knowing they’re two things that both had material impacts on the world:

Finding out these phenomena are related would be a twist, except we know you are meant to intuit this, because Uzi does it!

An example of this being done well is the Cabin Fever insignias. Episode 3 is all about Doll and her strange powers, we learn that Uzi has the same powers and also share this necklace in common. This chains directly into the next episode where we get a quick flashback where Uzi figures out what the symbol means, and then they go investigate that location. Bing, bang, boom.

Personal

Ambiguous character motivations and expectations

This is far and away the most severe issue with the first half of the show: It is almost constantly unclear what people’s thoughts and motivations are. The sin is the effect — the viewer not understanding the motivations and goals of the characters, and so not having proper expectations — but there are a few different things that all cause this.

A common cause of this is characters communicating in ambiguous ways about their relationships with major plot elements.

Let’s start with the Absolute Solver, the main plot of the series. One of the first things we learn about disassembly drones is that they have this pseudo-magical auto-repair healing factor that worker drones don’t.

In the next episode, Uzi sees J’s Absolute Solver aftermath and makes the wild leap that the Absolute Solver is a program of some sort that manipulates matter in order to autonomously heal drones.

So — very basic question — what do our two disassembly drones think about this? N says he’s totally surprised by the snake-crab, and the fear that there’s something monstrous inside disassembly drones (besides their already monstrous vampirism) drives a wedge between N and Uzi.

Uzi asks N “what are you things?” and N does this strange ashamed runaway instead of acting horrified. It’s framed as him being embarrassed of his race category, but again it’s left unclear whether any of this is understood or expected.

N then goes to V and… sits in silence in the corner. Does this always happen? Had no disassembly drone ever sustained damage before? Now that it’s happened, do they think J was an anomaly, or are they in danger of the same thing? We’re led to assume this was totally new information for them, but we’re then led to believe that V is familiar with the solver snake-crab effect. So for N’s reaction to make sense, they’d have to have two totally different understandings of the world, despite their squad already working together so much they’ve created a whole corpse spire.

In the next episode, N asserts to V that “we can’t interact with the worker drones, we’re too dangerous.” Why has he started to think this? Presumably J, except that’s hardly more dangerous to the workers than the genocide they were already committing. Or did two things change simultaneously, and N’s changed both his opinion on worker drones in general and also his own nature? Why would arguing that they’re dangerous convince V, who is still doing the genocide?

These aren’t “plot holes”. Every character is allowed to be wrong about things and fail to communicate effectively with others. In fact, that can be very narratively interesting! That’s not what’s wrong here. The problem is the story is hidden from the audience. We don’t know who is doing what, and why. The overall plot is a mystery, but also every character interaction is a puzzle we don’t have the pieces to.

As another example, let’s look at V in the first few episodes. How are we supposed to conceptualize her? What’s her personality and motivation, other than “psychopath”? We get pretty direct exposition, from her, that she doesn’t recognize the symbol, doesn’t know about the Absolute Solver, and is still primarily motivated to perform the drone genocide.

Then Cabin Fever comes, and we get a nice emotional arc between Uzi and V. As V sees N and Uzi care for each other, her attitude towards Uzi shifts from predatory (for both pragmatic and possessive reasons) to one of accepting and even actively looking after Uzi. Classic character work.

it’s weird that they “fit right in”, right? more on that in a bit

(This is also a pretty big unexplained shift from the pilot. V went from not caring about N at all to actively possessive about N, and keeping secrets from him to protect him, for some reason. Now, when N asks about anything, the answer is “stop prying into that stuff.” I think it’s just a retcon, but it’s totally un-lampshaded, and it’s so contradictory that it leaves the audience without an understanding of the character.)

The problem is, in the middle of that Cabin Fever emotional uzi-acceptance arc, the main plot of the episode is Uzi’s newly-discovered Solver powers manifesting in strange fleshy ways that V recognizes and wants to destroy, for reasons she doesn’t disclose to anyone else.

So it suddenly becomes very hard to get a non-contradictory idea of what V thinks or wants. Is she reacting to Uzi’s new suspiciously disassembly drone-like traits? No one knew that could happen at all. Or is she reacting to the parts of her transformation that are anomalous? Or her solver powers (even though V was fine with that earlier)? Or the fact that she goes on a vampiric killing spree and eats several of her classmates (even though V also does that)?

All those things happen at once, by the way. And there are reasons for all of them to be disturbing to different people for different reasons. There’s a lot to react to, but not only is it unclear what V is reacting to, it’s unclear what exactly her reaction is. V and N have a conflict/conversation with incredibly tightly packed emotional swings and reactions, but none of them tell us anything meaningful about the characters or plot, because everybody is all over the place all the time.

And because all the characters are keeping secrets from each other, it’s never revealed to the viewer what the conflict is, which is a pretty important component, narratively.

Also, in a move that felt like they just did it to screw with me, we then see Uzi use these same fleshy powers that sent her into an insane corruption rampage masterfully and casually, with no one (including V) reacting or mentioning it.

This problem keeps happening. Episode 3 is a whole tangled mess of this, specifically in regard to Lizzy. There’s a subplot where she’s manipulated by V to give V the chance to genocide their prom, but at the same time Lizzy is working with Doll, who is openly showing Lizzy her insane vampire murder life. Meanwhile, all these plots work together to accomplish totally disjointed set of goals (including V at prom) that didn’t require the murders that constituted the main plot of the episode.

With full hindsight, my best-guess answer to all that is: V and N do have two sets of information, N didn’t know about the solver and V did. But, somehow, V didn’t know about the most distinguishing feature of the solver, the symbol. (This was retconned without anyone telling the audience, maybe?) Moreover, when Uzi began exhibiting monster traits, V recognized them as related to Cyn, who she was trying to keep N safe from(???). She then had to weigh her two significant motivations — her care for N, and her antagonism toward Cyn — and made the gamble to trust Uzi to satisfy the former at the expense of risking vulnerability to the latter. Doll’s plan made no sense because the purpose of the episode was for Doll to do a big dramatic heel-turn for the audience, and Lizzy is just a psychopath.

This is a very complicated answer and not one you can formulate when you first watch the show, which means you don’t have enough information to understand the characters or conflicts.

In the middle of writing this I watched Jacob and Leo Untangle the Brilliance of DEVS, a retrospective on the TV show Devs, and Jacob Geller made this comment I agree with:

And the show does that [thing I want Sci-Fi to do more which] is just have characters talk through ramifications of things. Like, you know, I want to hear those conversations. And so them kind of having all the arguments that you would have I think is so interesting.

If having these conversations so consistently is part of what makes Devs engaging, characters refusing to ever discuss the implications of their world makes it that much harder to engage with it. The drones are all encountering huge, crazy new concepts that should totally realign their views of the world, and they don’t communicate how they’re dealing with that.

Social tones and reaction humor

There’s another category of narrative confusion that’s tightly related to all this. I said earlier that I didn’t have an issue with the humor of the show. Poking at tropes can be fun, turning social interactions into clownish performances can be funny, etc. No problem here. What is a problem is when these gags aren’t in service to the main task of communicating the story. And this happens a lot.

In the early show, the most significant dynamic to understand in this whole fictional world is how the societies of the worker drones and the disassembly drones relate to each other. These groups and their relationship is the worldbuilding of the show, and defining and later subverting it is absolutely fundamental.

In the pilot this is spelled out. Uzi’s full name is Uzi Doorman, because she’s from the vitally important Doorman family, the family that makes the giant doors to protect the workers from the titular murder drones. Their entire society is defined by worker drones defending against the existential threat of disassembly drones, who are actively committing genocide against them.

But Uzi delivers all that exposition before anyone even knows disassembly drones can speak. Most of that backstory is eventually contradicted or disproven, so it’s not at all a set-in-stone truth given by a reliable narrator. Subverting the worldview expressed in the opening exposition is a core thread of the show’s plot.

So, given that this “interspecies” relationship a core part of this world that’s in flux throughout the series, the audience needs to understand its norms. Especially — as is the case in Murder Drones — that relationship is the crux of a radical societal shift. So it’s a problem when every interaction between workers and disassembly drones is played for laughs.

Right off the bat, immediately after leading an invasion force into the bunker that slaughters its citizens, N is granted access by the guards by giving a cute face and saying “sorry” nicely.

Uzi’s father takes her to prom, where she’s faced with the question “how could you side with the murder drones, they killed our families?” This is an extremely valid question, but tonally it manages to clash with the episode, because everyone is seemingly okay with everything, all the time.

At prom, Lizzy helps reassemble a damaged V while chiding her for her attempted mass-murder. This whole conversation is significantly less important to everyone in the room than being mean to N.

A minute later, disassembly drones serve as chaperones of a school field trip as a pretext to explore the area. Everybody hangs out and does fun camp activities. At this point, V has not stopped doing the genocide, and actively murders and eats children during the trip.

This is the same trip where Uzi becomes a vampire and goes on a killing spree, murdering and eating many of her classmates. This is never dealt with in any capacity.

It all adds up to a bullet point I had labeled “people are generally cool with stuff they shouldn’t be”. It’s supposed to be a combination of clowning, trope humor, and plot lubricant, which are all fine in moderation. But in Murder Drones, the way this permeates the story — including plot-crucial points — creates a genuine problem. Fundamentally, it’s not clear what kinds of behaviors are normative in this world and what’s considered a meaningful violation of standards. Which makes it unclear what those standards are, which makes it hard to understand the world the story is taking place in. Which matters!

Plot

Human twist doesn’t land

In the very first episode, it’s ambiguous whether humanity died out or just the humans on the one exoplanet. This is a critical plot point!

“Ambiguous” is me being generous here. Uzi says, outright, that “all humans” were killed, and it was easy to pick up where “they” (humans? humanity?) left off. When Tessa shows up, that’s a twist, and so the assumption has to change to be that humans are still around somewhere, maybe in colony ships. (Ironically, “Tessa” showing up doesn’t mean anything for the state of the human race, actually.) So, when Tessa drops the big twist that Earth was destroyed just like the drones’ exoplanet, it doesn’t land. It’s not a twist if it was completely reasonable to assume that had been the case the whole time.

This might just be a victim of a chance in plot direction since the pilot. But if that’s the case, by the time they got to episode six out of eight and were ready to reveal the reveal, they needed to lampshade this somehow in order to make the twist land. Instead, the pieces just don’t connect well, at the expense of the story.

Eye colors

I’ve already mentioned how the blue lighting hurts scene recognizability. But here’s a specific bone I have to pick with lighting choices not just affecting scene readability, but directly hurting the communication of the story. Here’s N in a flashback in episode 2:

It’s an important plot beat that N’s eyes are white and not yellow in this shot. Unfortunately it’s literally impossible to tell that’s the case, because the scene is lit with yellow incandescent lights, so everything white is yellow anyway.

Our best chance at noticing something here is to compare N’s white eyes with yellow eyes directly in this same lighting, which we fortunately get. But here’s what that looks like:

As a visual language, this is illegible.

The only screenshot I was able to get where you can see the difference at all is this one brief shot where both characters are in the same shot and lighting at the same time:

But as a point of reference, here’s an earlier shot showing V with white eyes compared to N’s yellow:

You can see the same kind of contrast here, except in this shot it’s meaningless. Both sets of eyes are still supposed to be yellow here. Which means that major plot point comfortably falls into the margin of “animation error.” That’s real bad!

Mechanics

Too many similar mechanics

This is the cousin of the visual similarity problem. There are a lot of mechanical effects in Murder Drones. Big ol’ tech tree. But there are a lot of different mechanical things that look the same but have totally different causes, or a single cause that can be expressed in very different ways.

Too many kinds of regeneration are introduced at once. In episode 1, we get two different kinds of healing: N’s liquid metal self-repair is one distinct ability, but then the healing saliva is another distinct repair mechanism that works on other units too. (This never comes up again.) One episode later and we get the snake-crab, which seems to be J’s core using an as-of-yet unexplained matter manipulation ability to rebuild her robot body. We then learn that the core is controlled by an autonomous program, not J, and then much later we learn that it’s not a program, but an undefinable eldritch entity. Uzi also gets her own regeneration ability, which uses a distinct soldering effect.

Ultimately, the significance of death (writers take note: this matters) is very muddy. In addition to all the ways drones (and non-drones!) can regenerate what should be fatal damage, we see in J that some robots can literally be replaced with duplicate copies even after permanently killed. It’s also implied that worker drones might have access to the same powers as disassembly drones, but the extent of this isn’t clear, so it’s never obvious if any particular damage is significant or not.

Then, halfway through the series, the idea of cores as a standard worker drone component (as opposed as exclusive to either disassembly drones or snake-crab monsters) is introduced, and now that’s the only time death is significant.

And yes, cores are another unacknowledged retcon. The pilot shows a bisected, coreless worker drone. But even not including that, J’s core being the Absolute Solver instead of having J’s own personality is inconsistent and doesn’t make any sense, especially since J wasn’t ever even a solver host.

Meanwhile, with regard to death, the Absolute Solver seems to transcend the idea of bodies entirely and is usually freely possessing multiple robots simultaneously. Until damage to one particular possessed drone’s core effectively seals her away despite that.

But there are also issues with mechanics less significant than death itself that still play a role in the mystery.

Episode 5 introduces the idea that magnets knock drones out. Episode 6 introduces sentinels which also knock drones out, but also magnets don’t do that anymore, they’re just mild sedatives. Again, the problem isn’t that this is a “plot hole”, it’s that it’s the same mechanic being too different too quickly, making it hard to understand the world as a coherent system.

Disassembly drones’ “vampirism” means they have to consume oil, specifically to prevent from overheating. (Uzi picks up this trait too as she begins to use the solver.) We see drones attack and eat other drones to sate this need. The problem with this is we later see this exact behavior in Cyn’s drones during the culling of Earth, and it’s against fleshy, bloody humans.

This obviously doesn’t involve ingesting drone oil, and seems like it couldn’t have any of the physical effects oil is supposed to give them. So we have the same action done in two different ways, signaling a thematic parallel but not actually paralleling any of the same ideas. Bad triangle problem.

An exciting and marketable thing disassembly drones can do is turn their face into an elongated X, to signify that they’re little rascals. This starts as a trait unique to disassembly drones, but then in a big reveal Uzi does it too.

Wow, is she turning into a disassembly drone??? No, she’s turning into a third kind of bat-thing that’s mechanically very similar to a disassembly drone (face, wings, vampirism…) but distinct in a few obtuse ways that aren’t explained (fleshy, weaponless, possessable…).

As for the elongated X face, we’re given a lore dump that says it’s an indicator of a “Faulty OS String”. It’s very nice to have information like this conveyed at all, but here it doesn’t land, because when we see it in-universe it’s an expression rather than a consistent indicator. Also, we don’t know what an OS String is, or why that’d be relevant. The implication is disassembly drones have theirs changed, I guess, but nothing ever indicates why anyone would have done that or why it’d show up on Uzi.

Transformations

Similarly, there are too many alternate forms of things. Disassembly drones seem able to transform in a number of ways by design: their wings can be deployed or undeployed at will, and their arms can transform into seemingly any kind of weaponry. That’s all supposedly standard, but then there are more transformations added in that are key to the plot.

In episode 2, we learn disassembly drones can apparently become snake-crab monsters. In episode 3, we learn that worker drones can become some sort of teleporting psychokinetic ghost. In episode 4 we see a worker drone transform into a beastly form that resembles disassembly drones but is still very different, and in episode 5 we see that our disassembly drones were originally maids and butlers, which are called worker drones but are very clearly physiologically different from all the other worker drones we know.

Actually, let me dig into the maid droid angle, because that’s very representative of this problem. The flashback scenes were supposed to be the big reveal that disassembly drones were originally worker drones. But instead they’re shown to be an entirely different third thing that doesn’t fit anywhere within any of the previously established taxonomies. The flashback servants have the stature of disassembly drones, but the limbs of worker drones, and a job and environment that’s also totally new.

Narratively, this is supposed to be the “A was B all along” twist, but the introduction of the new variant breaks the “all along” part. It’s like if planet of the apes revealed at the end that they were on a planet that’s a lot like earth but still a different place. So it doesn’t click. None of the pegs fit in the holes, because every peg and every hole is a different shape every time. When everything is novel all the time, the viewer doesn’t get a frame of reference.

All of these effects have different triggers and different significances to the plot, but none of them are explained or understood (by characters or viewers) before the next one is introduced. Most of them are justifiable in hindsight, but in an “ok, I suppose that justifies how that was able to work” way, not in an “oh, that clicks into place, that’s so clever” way.

And they could have clicked into place in a satisfying way. The transformation designs are great and the logic behind them is mostly wired up. They’re 90% of the way there, but that missing 10% noticeably takes the edge off. Again, the piece that’s weak here is how well this world is communicated to the audience.

There’s an attempt to unify a lot of these mechanics and effects under the eldritch “solver” label, but…

Solver powers are very poorly defined

So what actually is the “Absolute Solver”? I might put this question under “mechanics”, except one of the things the Solver is is a sentient person! The same name is used for both the main antagonist of the series and the main supernatural mechanic. It’s the whole metaplot, so it’s important to know what it is. Even in retrospect, this is remarkably hard to do!

So, by my count, here’s what all is explicitly referred to by the name “Absolute Solver”, in order of appearance:

0: A boolean variable in worker drones’ OS that can be toggled (probably retconned)

- Disassembly drones’ autonomous repair functions (saliva, liquid metal, etc.)

- A sentient emergency-repair system (snake-crab) to reconstitute disassembly drones triggered by major damage

- A set of consciously-invoked abilities (matter manipulation, teleportation) some drones (Doll, Uzi, Cyn) are able to tap into

- A non-sentient layer of OS programming in disassembly drones to suppress and wipe certain memories

- An eldritch entity whose conduit is mutated disposed AI who possesses drones

One thing these all have in common is they’re all reliably sick as hell any time they’re on-screen and don’t think for a moment I don’t appreciate that.

Some of these are compatible with each other, but not all of them at once. That’s right, it’s Bad Triangle time!

- 1 and 4 could be the same thing, but they can’t also be the same thing as 5, because disassembly drones who have 1 and 4 aren’t ever possessed and seemingly can’t be.

- 2 and 5 seem like the same entity, with 2 just being 5 possessing a drone core, except 2 is embedded in (some?) disassembly drones and 5 is not. We also see disassembly drones hit the condition to trigger 2, but nothing happens.

- 3 is probably a property of 5, and drones with 3 are either actively possessed, have been possessed previously, or are descended from a once-possessed drone. But worker drones with 3 don’t have the abilities of 1 or 2.

- Uzi using 3 seems to make her a conduit for 5, except we see two other drones (Nori, Doll) freely using 3 without triggering or risking possession.

- The eldritch nature of 5 consistently has themes of fleshiness and corruption, especially in Uzi and Cyn. We see this fleshy effect on all drones with any of those numbered traits.

Even if we’re open to a more complex mechanical than the “Absolute Solver” being any cohesive idea, lots of other things prevent any reasonably simple model from working. Once Uzi exhibits 3, she acquires the disassembly drone vampiric weaknesses of burning in sunlight and having to consume oil to keep from overheating. But disassembly drones don’t have any of those powers, and Uzi never exhibits any of the abilities of disassembly drones.

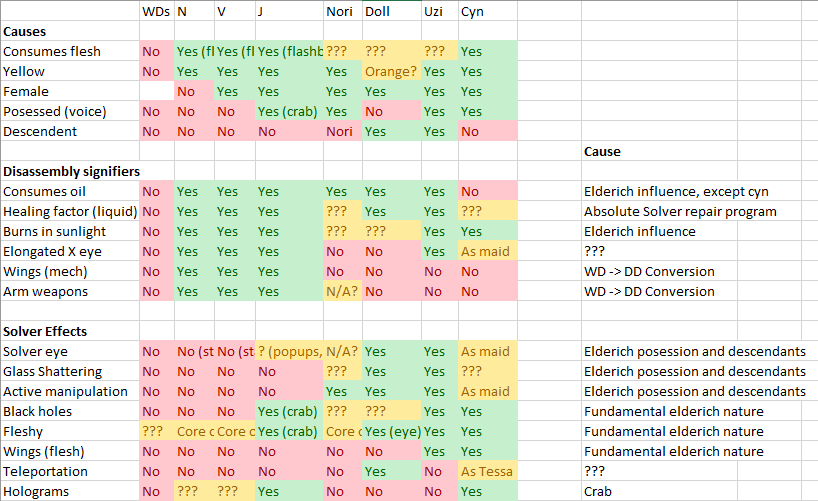

Once we’re away from a strict definition, we have to factor in all the signifiers and associated symbology, and it works less and less. I actually went through the whole series a third time just to fill out this table to try to figure out what powers correspond with what causes, and it just doesn’t work.

This leaves me unable to answer really basic questions. Are DDs hosts for 5, like Uzi, Doll, and Cyn? solver!Tessa says that no, only Uzi is a target, and most evidence agrees and suggests either special experimentation or a genetic component is required, but J proves otherwise with 2.

“Having the Solver” (3) lets Doll and Cyn teleport at will, but not anybody else. What’s the common factor unique to those two but not Uzi and Nora? Nothing! I checked the table!

This isn’t a dumb powerscaling question, this is literally one of the core mysteries of the series. And if I can’t even pin it down with three rewatches and a spreadsheet, a new viewer won’t be able to intuit any of it. And that’s what matters, not my autistic little spreadsheet.

Magic

So if all these powers are cool, why doesn’t it click? This question got me thinking about magic systems in fiction in general.

These robots and powers do form a magic system. Not counting the more explicitly supernatural, eldritch properties of the Solver, the drones and their various abilities are all part of one world, and every mechanic relates to the others. So it’s a system, but it is also magic: these are not physical systems and rules the audience is already familiar with, because they don’t exist in our world.

So if you have a new system of extra-natural abilities, and you want to use that as background for a larger story, how do you write that? This is not a new question. Looking at how people have answered it led me to Sanderson’s Laws Of Magic, a set of essays on writing and communicating magic systems in fiction, the point being that there are best practices for writing magic that works with the narrative:

Sanderson’s First Law As a storyteller, I want a setting element that is narratively sound and which offers room for mystery and discovery. A good magic system should both visually appealing and should work to enhance the mood of a story. It should facilitate the narrative, and provide a source of conflict.

The laws are:

- An author’s ability to solve conflict with magic is DIRECTLY PROPORTIONAL to how well the reader understands said magic.

- Limitations > Powers

- Expand what you already have before you add something new.

For the purposes of Murder Drones, we can tick #2 off as done, since Uzi’s solver powers are explicitly corrupting, and the narrative does a good job at framing an internal and external conflict around the tradeoffs involved in using them. Of the remaining two, a new power isn’t usually presented as a solution to conflict, so I think #3 is what Murder Drones has the most trouble with.

I think a lot of the reason this is an issue is due to the “indie rush” I talked about at the beginning of this essay. If you have a lot of good ideas but fit them into too small a space, they don’t have room to breathe and build on each other.

Sanderson’s point here is not just about pacing out how frequently you introduce new mechanics, but also that it’s often better to develop and extrapolate the mechanics you already have. Keep the rules, play with the consequences.

Sanderson’s Third Law of Magic Often, the best storytelling happens when a thoughtful writer changes one or two things about what we know, then extrapolates purposefully through all of the ramifications of that change. … Extrapolating, to me, is about asking the “what happens when” questions. … Instead of giving every character a new power, can you have different takes on the same powers, used in different ways?

As I’ve been discussing, Murder Drones pathologically avoids letting characters work through the ramifications of things. It’s difficult just understanding a character’s thoughts and motivations, and the show usually introduces new ideas and characters instead of doing new things with the tools it’s already introduced. (See: Alice.) In other words, it’s good at making “what happen”, but is weak at tying it to the “when”.

I really like the point here about exploring variations of established mechanics, which seems like something that would fit into Murder Drones very well. N and V have the same sets of abilities as disassembly drones, but they express themselves with them very differently. N is very utilitarian and stays in “civilian mode” most of the time, whereas V tends to stay in wings-out, arms-rotating combat mode whenever there’s any excuse.

The king of personality though would be the Absolute Solver itself. The triangle-glyph matter-manipulation power of people actively wielding the Solver is extremely versatile, and almost a magic system in and of itself.

Wed Jun 21 19:01:00 +0000 2023robot witchcraft was used in the making of this concept art

There’s a lot of potential here for variation as a narrative tool. What if one drone used editing as their go-to action, and another just used translation as telekinesis? You can use the flexibility of the power as a narrative device here, use specialization and style as a method of characterization. The one thing we get that’s close to this in the story is the null bomb Cyn frequently uses, but that’s more of a special case than an extension of the existing toolset. So this strikes me as an angle that could have easily created some rich narrative and characterization, but was left unused.

So what?

I don’t know! I liked murder drones and I thought it was interesting to think through all this.

Like I said in the opening, I don’t even know that any of this means that the show is “bad”. But I love that you can notice something feels off and identify the reasons that might be. And I also like identifying how some of these mechanical issues in communicating the story could be mechanically fixable, even if this particular show may not have had the resources to do it.

fandom

fandom