Gris

Last week, looking for a game to play to wind down at night in bed, I went through my backlog of unplayed Steam games and filtered for something that looked relaxing. I fished out Gris.

Gris is intriguing, atmospheric, and gorgeously animated. It’s a beautiful indie title.

And I kinda hate it?

Gris rubs me the wrong way, I think, because of what it says1. Gris is a game about grief. It’s very clearly a game about grief and the process of growth and recovery. Although, there’s little “textual” evidence from the game to easily demonstrate this, since Gris has no expository dialogue. There is no text in Gris at all. But there is a narrative, even if the events in the game itself are allegorical rather than literal.

Gris’ store description simply says

Gris is a hopeful young girl lost in her own world, dealing with a painful experience in her life. Her journey through sorrow is manifested in her dress, which grants new abilities to better navigate her faded reality. As the story unfolds, Gris will grow emotionally and see her world in a different way, revealing new paths to explore using her new abilities.

GRIS is a serene and evocative experience, free of danger, frustration or death. Players will explore a meticulously designed world brought to life with delicate art, detailed animation, and an elegant original score. Through the game light puzzles, platforming sequences, and optional skill-based challenges will reveal themselves as more of Gris’s world becomes accessible.

In the game, Gris’ image of herself, in the depicted form as a giant statue, is literally shattered, hurling a wounded Gris into a hostile environment. Throughout the game she gradually rebuilds herself — her world (depicted by color), her image (depicted by the statue), and her physical body. And eventually, once everything is scarred but healed, floats off into the sky into an ambiguous future.

The game is defined by this continuous, constant progression of gentle healing. Gris is a puzzle platformer. As you progress, you regain your ability to walk, then run, then jump. The world starts colorless, but then regains its reds, then greens, then blues, then yellows. The constellations return, and as the credits roll you get the Steam achievement for “Acceptance”

Every mechanic and story beat in Gris works together to describe the process of “working through” the stages of grief. Gris says that grief is a process of a thing, to be worked through, that can be overcome, that you recover from.

And you do all these things painlessly. Did you catch that line in the store description, that “GRIS is a serene and evocative experience, free of danger, frustration or death”? That is absolutely, painstakingly the case. There is no health, no frustration, no death, no real setbacks of any kind. There are puzzles, but none that take more than a minute or two of low-intensity movement to complete, and there are never any meaningful consequences for failing any given step.

Whenever the platforming is particularly vertical or interesting, you can actually see how every bit of world geometry is constructed with guardrails, to keep you from harm but also keep you carefully attached to the path.

You can’t fall off to the left, you can only turn around and go back to the plot.

You can’t fall off to the left, you can only turn around and go back to the plot.

But none of that is right, is it?

Grief

Now, I’m not an expert on grief, and frankly I’m not willing to try to “solve grief” as background material for a blog post.

But in my experience, I feel like if you could recover from it, it wouldn’t be grief. Grief comes from real, significant loss.

Injury minor enough that it can be recovered from doesn’t cause grief, because it can be recovered from. Conversely, grief isn’t something that can be “healed”, almost by definition: if a loss could heal, you wouldn’t grieve it. Grief comes when in some way, along some dimension, things worsened such that they will never be right again.

Mourning is one thing; it’s a way we engage with a circumstance. But grief is not participatory, it is something inflicted on you by a circumstance so overwhelming that you cannot work “with” it. And interacting with grief — whether it dominates you or whether you push through it — is invariably a painful process. My experience of continuing after grief is less “repaired” and more “persisted nevertheless”

So an on-rails story about grief as a process of a pastel-perfect inevitable recovery doesn’t just rub me the wrong way, it’s almost offensive. How dare you expect this of me? How dare you expect this of anyone? Who do you think you are to demand people understand grief as this toothless thing you’ve made it into?

Diminish

That’s probably where I would have left it — mild annoyance — except that just days after finishing Gris, I discovered the web series Diminish. And then it clicked.

Diminish is an unfiction project about a man named Will recording his playthrough of the game Diminish: the game his twin sister made for him before she died of cancer.

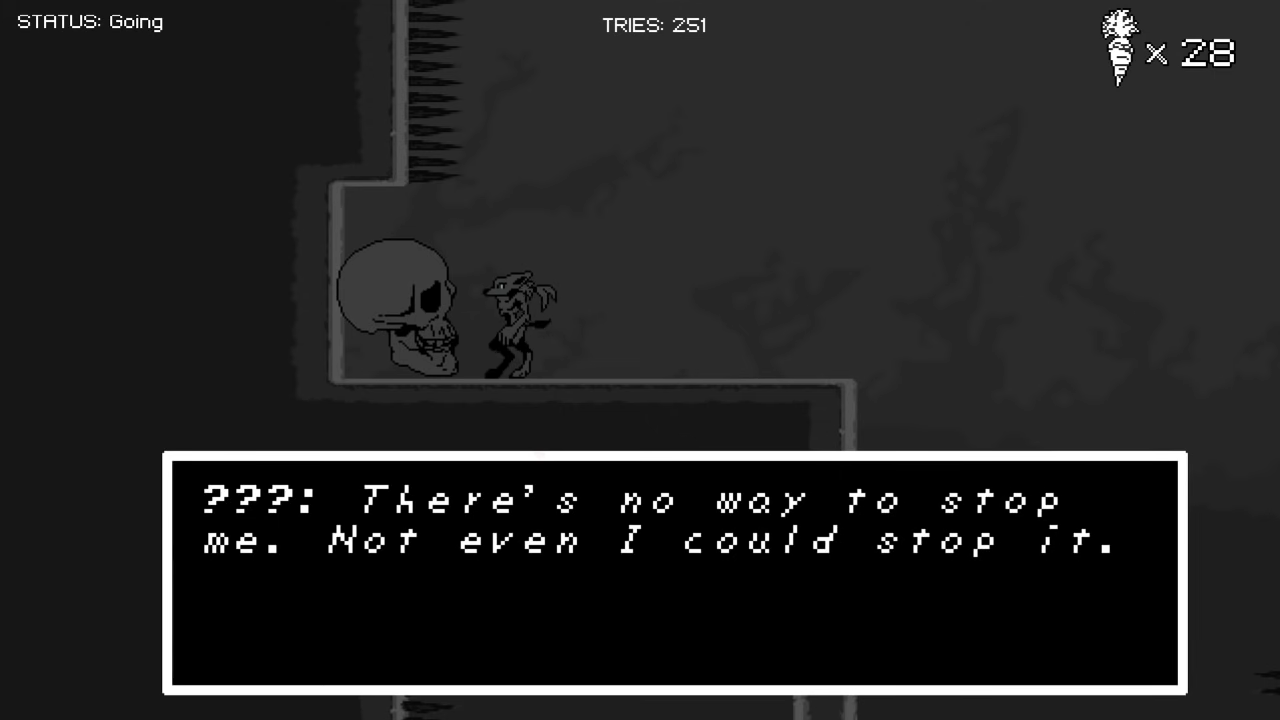

Diminish is not a gentle puzzle platformer. It’s what Will describes as a “rage game”: an extremely precise movement platformer in line with games like Celeste or IWBTG.

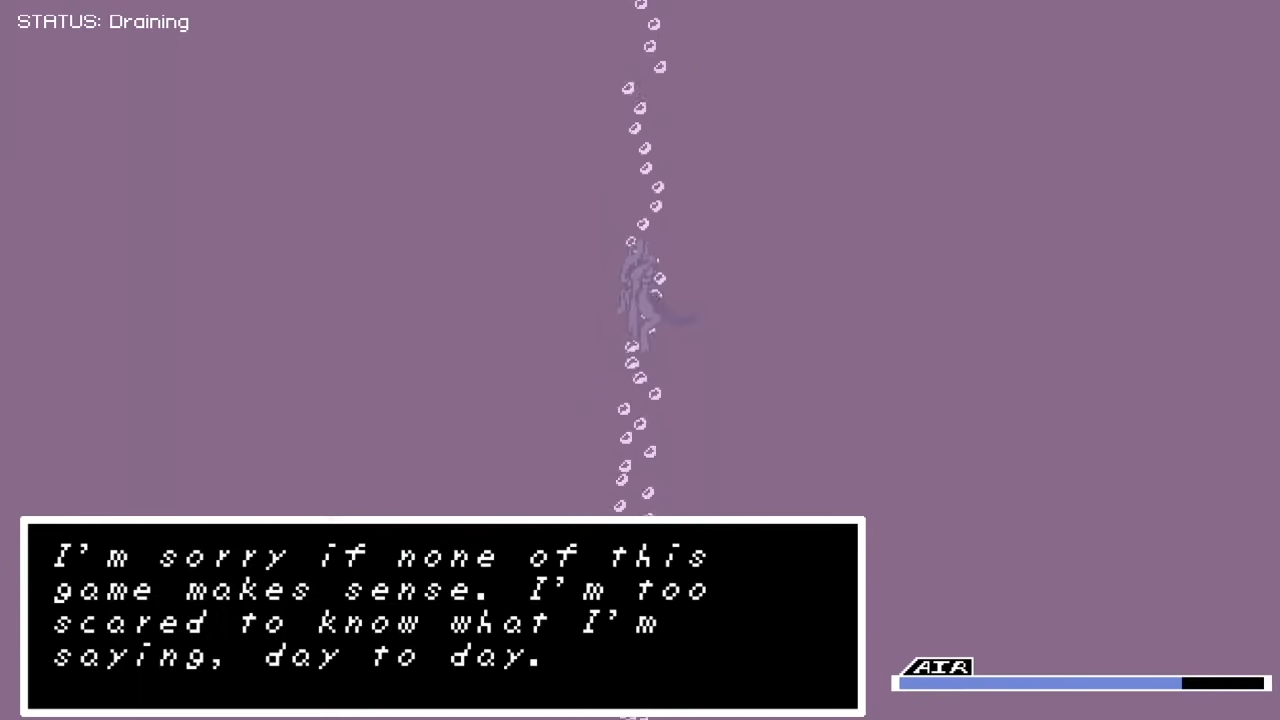

Diminish is also about grief, but it feels like a much more serious meditation on the subject. It’s thematically poignant both mechanically and thematically, with the focus dipping between mechanics and text as Will either engages directly with the mechanics of the game or thinks out loud about its context in his life.

Diminish hurts. Diminish is painful and difficult and full of constant painful setbacks. It’s extremely unforgiving, and Will’s progress is constantly being reset (sometimes very painfully) back to the beginning. Frequently, he’ll get just a little bit further and be blindsided by something he’s never seen before and can’t react to, and gets sent all the way back to the start. And there are virtually no checkpoints, so the difficulty only ever ramps up. Best case scenario, he comes back with a little more information, or experience, or the world changes out from under him.

Diminish - Act 1, Ep 2 Oh god, and here we are again, this is the worst part of rage games, it’s when you finally get farther than you’ve ever been before and then… when you inevitably are too nervous to be able to get past that part, you’re sent back to the same place and… that like, you’re stuck at the first part of it, for like the next 50 years and then when you DO get back to where you were, you’re… there’s so much pressure built up from the fact that it took you so long to get back there then you have no chance to perform well enough to make any progress again. And it’s happening as we speak.

Throughout the game, Will is grappling with the death of his sister in real and emotionally significant ways. Between the metaphorical wrestling with her in the form of her work and the literal dialogue describing her experiences, every interaction with the game feels like interacting with her, and implicitly also her tragic loss. And, as she was designing and writing the game, Will’s sister was working through her own grief at her own death, and it all shows in her work.

For me, diminish invoked a very powerful meditation on the idea of “survival”. At one point, Will describes people telling him that he “can survive more than you think”, a thought he found offensive because his sister wasn’t able to survive something so small. Just like the mapping of the perceived size of the mistake to the impact of the consequence, it’s not up to us. But it turns out there’s a lot we can survive, and a lot we can’t survive, and reality doesn’t care if our understandings of which is which don’t line up.

Apollo, the player character in the game, is himself immortal. From his perspective, this is sometimes really, really bad. And this is so poignant for me, because that is what grief is like. It feels like it’s so tremendous that it should just kill you, that the world should just be in a fail-state, but then it isn’t. You don’t die, you don’t reset, you just have to keep living.

But after watching Diminish, for the first time in forever, I feel like playing a little Celeste.

Celeste

Gris and Diminish provide a great rise-and-fall. Two things to contrast. Which means this doesn’t fit and might even spoil the structure of the article, but I want to talk about it anyway.

Farewell spoils Celeste for me because I know I will never beat it. Because ironically Farewell, too, is about grief.

I got what I know now to be 1/10 of the way through Farewell before getting stuck, and then watched a video of the rest. I will never be able to perform to that level. Maybe, if I could spend months developing the skill, but it’s not worth it. That would be a waste of time, and the death counter already makes Celeste feel expensive to play. There’s no point in getting good enough to achieve something practically useless. There’s no point in climbing the mountain.

Inevitably, I play Celeste until my hands hurt, ask myself why I’m spending a day grinding at what comes down to arbitrary button inputs, and then stop. I have to ask myself questions about whether playing a game is worth the time investment, and when you have to think about that you’ve already lost.

And this same tension is reflected in the plot of the game, sorta. The main conflict in Celeste isn’t climbing the mountain, it’s Madeline’s stubborn determination to do something she’s ill-equipped to do for no reason.

Determination in the face of an impossible challenge is admirable and inspiring if the goal is worthwhile, and so if you see Celeste as metaphorical for pursing something you need (read: trans allegory). If you can overcome self-doubt; if you can break out of a constraint you’ve put on yourself and grow beyond a box you were in, that’s good. And those are both fantastic reads of the game.

But what happens when you don’t need to reach the peak? What if you don’t get to see a unique view and the mountain doesn’t represent inner growth? What happens when the mountain is just a mountain, the bird is just an imaginary bird in a dream, and being willing to sacrifice everything in dogged pursuit of the goal is demonstrably unhealthy?

Farewell starts to ask that question, but doesn’t really answer it.

If you get to a goal, is that going to satisfy you? Goals you set for yourself can’t bring back what’s lost; that’s just bargaining. Will you just keep getting offended at a world that refuses to restore what it took, no matter how many goalposts you draw on it?

Because there’s no alternative. You can’t construct your way out of it, because you can’t restore what was lost. That’s grief.

Determination won’t give you what you need, because you can’t get what you need. You have a need which is suddenly unmet, and then you stay like that, forever. What are you going to do? Do you suffer, or do you shrink, diminish, until you don’t have the same needs and are lesser for it? That’s grief.

But who knows. Even with all that, nothing feels quite like that last climb to the summit. Maybe our needs aren’t being met anyway: we’re creatures bound to our relativism, and if we could view ourselves objectively, the grief we’re aware of would only represent infinitesimal fraction of what’s missing. Maybe we can’t survive things we think we should, and we can survive things we think we can’t. But it’s not a process the world holds your hand through. It’s not easy. It’s definitely not easy.

-

By the way, engaging with a work of art in a way that you feel the ideas it’s communicating clearly enough that you can take specific issue with them is excellent. It’s maybe the best way of engaging with art. ↩

gaming

gaming