AI is a huge subject, so it’s hard to boil my thoughts down into any single digestible take. That’s probably a good thing. As a rule, if you can fit your understanding of something complex into a tweet, you’re usually wrong. So I’m continuing to divide and conquer here, eat the elephant one bite at a time, etc.

Right now I want to address one specific question: whether people have the right to train AI in the first place. The argument that they do not1 goes like this:

When a corporation trains generative AI they have unfairly used other people’s work without consent or compensation to create a new product they own. Worse, the new product directly competes with the original workers. Since the corporations didn’t own the original material and weren’t granted any specific rights to use it for training, they did not have the right to train with it. When the work was published, there was no expectation it would be used like this, as the technology didn’t exist and people did not even consider “training” as a possibility. Ultimately, the material is copyrighted, and this action violates the authors’ copyright.

I have spent a lot of time thinking about this argument and its implications. Unfortunately, even though I think that while this identifies a legitimate complaint, the argument is dangerously wrong, and the consequences of acting on it (especially enforcing a new IP right) would be disastrous. Let me work through why:

The complaint is real

Artists wanting to use copyright to limit the “right to train” isn’t the right approach, but not because their complaint isn’t valid. Sometimes a course of action is bad because the goal is bad, but in this case I think people making this complaint are trying to address a real problem.

I agree that the dynamic of corporations making for-profit tools using previously published material to directly compete with the original authors, especially when that work was published freely, is “bad.” This is also a real thing companies want to do. Replacing labor that has to be paid wages with capital that can be owned outright increases profits, which is every company’s purpose. And there’s certainly a push right now to do this. For owners and executives production without workers has always been the dream. But even though it’s economically incentivized for corporations, the wholesale replacement of human work in creative industries would be disastrous for art, artists, and society as a whole.

So there’s a fine line to walk here, because I don’t want to dismiss the fear. The problem is real and the emotions are valid, but that doesn’t mean none of the reactions are reactionary and dangerous. And the idea that corporations training on material is copyright infringement is just that.

The learning rights approach

So let me focus in on the idea that one needs to license a “right to train”, especially for training that uses copyrighted work. Although I’m ultimately going to argue against it, I think this is a reasonable first thought. It’s also a very serious proposal that’s actively being argued for in significant forums.

Copyright isn’t a stupid first thought. Copyright (or creative rights in general) intuitively seems like the relevant mechanism for protecting work from unauthorized uses and plagiarism, since the AI models are trained using copyrighted work that is licensed for public viewing but not for commercial use. Fundamentally, the thing copyright is “for” is making sure artists are paid for their work.

This was one of my first thoughts too. Looking at the inputs and outputs, as well as the overall dynamic of unfair exploitation of creative work, “copyright violation” is a good place to start. I even have a draft article where I was going to argue for this same point myself. But as I’ve thought through the problem further, that logic breaks down. And the more I work through it, every IP-based argument I’ve seen to try to support artists has massively harmful implications that make the cure worse than the disease.

Definition, proposals, assertions

The idea of a learning right is this: in addition to the traditional reproduction right copyright reserves to the author, authors should be able to prevent people from training AI on their work by withholding the right.

This learning right would be parallel to other reservable rights, like reproduction: it could be denied outright, or licensed separately from both viewing and reproduction rights at the discretion of the rightsholder. Material could be published such that people were freely able to view it but not able to use it as part of a process that would eventually create new work, including training AI. The mechanical ability to train data is not severable from the ability to view it, but the legal right would be.

This is already being widely discussed in various forms, usually as a theory of legal interpretation or a proposal for new policy.

Asserting this right already exists

Typically, when the learning rights theory is seen in the wild it’s being pushed by copyright rightsholders who are asserting that the right to restrict others from training on their works already exists.

A prime example of this is the book publishing company Penguin Random House, which asserts that the right to train an AI from a work is already a right that they can reserve:

Penguin Random House Copyright Statement (Oct 2024) No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner for the purpose of training artificial intelligence technologies or systems. In accordance with Article 4(3) of the Digital Single Market Directive 2019/790, Penguin Random House expressly reserves this work from the text and data mining exception.

In the same story, the Society of Authors explicitly affirms the idea that AI training cannot be done without a license, especially if that right is explicitly claimed:

Anna Ganley, Society of Authors CEO …we’re pleased to see publishers starting to add to the ‘All rights reserved’ notice to explicitly exclude the use of a work for the purpose of training [generative AI], as it provides greater clarity and helps to explain to readers what cannot be done without rights-holder consent.

Battersby does a good job here in highlighting that it is explicitly the training action being objected to, irrespective of potential future outputs:

Matilda Battersby, “Penguin Random House underscores copyright protection in AI rebuff” (Oct 2024) Publishing lawyer Chien‑Wei Lui, senior associate at Fox Williams LLP, told The Bookseller that “the chances of an AI platform providing an output that is, in itself, a copy or infringement of an author’s work, is incredibly low.” She said it was the training of LLMs “which is the infringing action, and publishers should be ensuring they can control that action for the benefit of themselves and their authors”.

Proposal to create a new right

Asserting that the right already exists is the norm. An approach — and in my opinion, a more honest one — is to argue that while it doesn’t already exist, it needs to be created. Actual lawsuits are loath to admit in their complaint that the law they want enforced doesn’t exist yet, so this logic mostly comes indirectly from advocacy organizations, like the (particularly gross) Authors Guild:

The Authors Guild, “AG Statement on Writers’ Lawsuits Against OpenAI” The Authors Guild has been lobbying aggressively for guardrails around generative AI because of the urgency of the problem; specifically, we are seeking legislation that will clarify that permission is required to use books, articles, and other copyright-protected work in generative AI systems, and a collective licensing solution to make this feasible.

Andrew Albanese, “Authors Join the Brewing Legal Battle Over AI” In a June 29 statement, the Authors Guild applauded the filing of the litigation—but also appeared to acknowledge the difficult legal road the cases may face in court. “Using books and other copyrighted works to build highly profitable generative AI technologies without the consent or compensation of the authors of those works is blatantly unfair—whether or not a court ultimately finds it to be fair use,” the statement read. Guild officials go on to note that they have been “lobbying aggressively” for legislation that would “clarify that permission is required to use books, articles, and other copyright-protected work in generative AI systems,” and for establishing “a collective licensing solution” to make getting permissions feasible. A subsequent June 30 open letter, signed by a who’s who of authors, urges tech industry leaders to “mitigate the damage to our profession” by agreeing to “obtain permission” and “compensate writers fairly” for using books in their AI.

Naive copying

There is also a black-sheep variation of this idea that insists training is itself copying the work. In this case there would be no need for separate rights and protections around training, since it’s a trivial application of existing copyright protection.

In their lawsuit against Stability AI, artists Sarah Andersen, Kelly McKernan, Karla Ortiz, Hawke Southworth, Grzegorz Rutkowski, Gregory Manchess, Gerald Brom, Jingna Zhang, Julia Kaye, and Adam Ellis assert that training itself is an illegal copy, and models themselves are “compressed” copies of original works.

In an interview, complainant Kelly McKernan explains that the lawsuit is explicitly a demand to require companies to negotiate a license to train AI on work, not a general stand against generative AI existing.

Emilia David, “What’s next for artists suing Stability AI and Midjourney” What do you want to see for yourself and how companies view, work and help distribute artists’ work after this lawsuit?

[Kelly McKernan:]

For one thing, I’m hoping to see that just the movement, in this case, is going to highlight the very problematic parts of these models and instead help move it into a phase of generative AI that has models with licensed content and with artists getting paid as it should have been the entire time.The judge acknowledges in the order that it has the potential to take down every single model that uses Stability, and I feel it can eliminate a whole class of plagiarizing models. No company would want to mess with that, and people and other companies would be more thoughtful and ask if the data in the AI model is licensed.

Setting boundaries: human learning is good

Unlike most people earnestly making the learning rights argument, proposals to expand copyright often don’t limit the proposed expansion in a human-reasonable way. This makes sense, since they’re focused on making progress in one specific direction. So just to establish a ground rule for discussion: in the reasonable argument I’m seeing reasonable people make, regardless of how we treat AI, people learning from art is a good thing. In a good-faith discussion, I’m assuming your goal is to defend against AI, not sabotage existing human artists.

The right for people to learn from anything they’re allowed to see is crucial, for what should be obvious reasons. People have an inalienable right to think. Human creativity involves creating new ideas drawing from a lived experience of ideas, designs, and practice. Influences influence people, and those people create new artistic work using their own skill and knowledge of the craft, which they own themselves. We shouldn’t need a special license for works we see to influence the way we think about the world, or to use published work to inform our knowledge of creative craft.

If humans were somehow required to have an explicit license to learn from work, it would be the end of individual creativity as we know it. In our real world, requiring licensing for every source of inspiration and skill would collapse artistic work down to a miserable chain-of-custody system that only massive established corporations could effectively participate in. That, and/or some kind of dystopian Black Mirror affair, where the human mind is technologically incapable of ingesting new information unless it comes with the requisite DRM.

People have the rights to own and use their own skills and abilities by default, unless there’s a very specific reason barring them from a particular practice. You have every right to learn multiple styles and even imitate other artists, for instance. But you don’t have the right to use that skill to counterfeit, forge, copy, or otherwise plagiarize someone else, because that action is specifically harmful and prohibited. This is all very straightforward.

Unfortunately there does exist an unhinged territorial artist mindset among people who feel an unlimited right to “control their work”, including literally preventing other people from learning from it. But the idea that people shouldn’t be able to learn from published work is genuinely evil, and to people seriously trying to argue for it are deranged.

The weird way Hitler particles keep appearing in artist discourse is fascinating, but probably a topic for another day. For now, suffice it to say this mentality exists and I do not respect it.

Not within existing copyright

Regardless of what new IP rights can and should be created, a reservable learning does not exist within copyright now.

Viewing rights

People are only able to learn from work we can observe in the first place, so let’s think about the set of instructional and inspiring work a given person/company has the right to view.

If you own a physical copy of something you’re obviously able — both physically and legally — to observe it. Examples of this are books, prints, posters, and any other physical media. You have it, it inspires you, you reference it, you’re golden. There are also cases when you don’t own a copy, but have the right to observe a performance. Examples of this are ticketed performances and theater showings, but also things like publicly and privately displayed work. If you visit a museum you can view the works; if you visit a library you can read the books.

When you post your creative work publicly (on the internet or elsewhere), you own the copyright (since it’s creative work fixed in a medium), but posting it publicly also means you are publishing the work. This scenario of someone having the right to view something but not owning a copy or any particular license is extremely common on the internet. If you put a work online, anyone you serve a copy to (or authorize a platform to serve a copy to) has the right to view it.

Just publishing something publicly doesn’t mean you forfeit the copyright to it. But you inevitably lose certain “soft power” over it, such as secrecy and the ability to prevent discussion of the work. But that doesn’t mean the work is in the public domain, and it doesn’t mean people have an unlimited right to reproduce or commercialize work just because it’s on the internet. Publishing a work does not mean you’re relinquishing any reserved right, except possibly licensing a web platform to serve the file to people. Putting work “out there” does not grant the public the reserved rights of copying, redistributing, or using your work commercially. Just because a stock image is on Google Images doesn’t mean you have the right to use it in a commercial product.

Fortunately I think this all maps pretty cleanly to people’s actual expectations in the medium. If someone posts art, they know other people can see it, but they also know the public isn’t allowed to freely redistribute it or commercialize it. It’s just public to view.

Unenumerated right

But talking about who does and doesn’t “have” a “viewing right” is a backwards way to think about it.

Copyright grants creators specific reserved rights. Without copyright, people would be able to act lawfully: do whatever they want to do as long as there wasn’t a specific law or contractual agreement against it, including copying creative works and using them commercially without permission. Copyright singles out a few rights — namely the reproduction right — and reserves them to the creator, who can then manage those rights at their discretion. People are still able to do whatever they want with creative works as long as there isn’t a specific law prohibiting it or a reserved permission they don’t have. They can’t reproduce work by default, but only because that right is explicitly reserved.

Reserved rights are enumerated: only rights explicitly listed are reserved. Non-reserved rights are unenumerated: they’re not on any comprehensive list, but you have a right to do anything unless there’s a specific prohibition against it. It’s allow-by-default with a blacklist of exception, not deny-by-default with a whitelist. You can’t stab someone in the eye with a fork, not because “stabbing” is missing from your list of allowed actions, but because “stabbing” is assault, which is explicitly on a short list of things you are expressly prohibited from doing.

If you hold the copyright to a work you are automatically granted a reserved reproduction right, and you can manage that right in an extremely granular way. You can reserve the right to make copies to yourself, or you can license specific parties to be able to copy and distribute the work by contract, or you can make a work generally redistributable under specific conditions, or you can relinquish these rights and release things as open-source or public domain2. Because the law allows you to explicitly reserve that particular right, and that right can be sublicensed, you retain extremely specific control over the specific behavior that right covers.

But only a few rights are enumerated and reserved by copyright. Viewing, like most actions, is an unenumerated right; you don’t need any particular active permission to do it, you just need to not be actively infringing on a reserved right. If you’re able to view something and there’s nothing specifically denying you the right, you have the right to view it. And the right to restrict someone from viewing something they’re already able to view isn’t one of the special rights copyright reserves.

Learning

Learning is another unenumerated right, and is nearly the same thing as viewing already. If you’re able to learn from something, you’re allowed to do so. And this unenumerated right can’t be decoupled from the viewing. Learning isn’t a reserved right, so you don’t need specific permission to do it. You have the right by default, and the only way for people to deny you that right is to keep you from experiencing the work at all.

You don’t have to negotiate a commercial license for work just because knowing about it influenced something you did. That’s not reserved, and so isn’t a licensable right. You don’t have to negotiate a license from the creator, because the creator isn’t able to reserve an “education” right they can grant you. It would be absurd if they could!

Fri Sep 29 23:16:07 +0000 2023Don't want to trigger anyone, but I have to confess that I trained my writing algorithms by reading other people's books, including countless books I didn't pay for.

All that means the right to learn is mechanically coupled to the right to view. Rightsholders can use the reproduction right to control who is able to view a work, but if someone can view it, they can learn from it. There’s no way to separate the two. You can’t withhold the right for people to learn and still publish material for them to view.

You have the right to use materials that you already have the right to view to learn the craft. If you buy a painting, or someone posts an image online, your right to view it (which you’ve been granted) is inextricable from your right to think about that image. It’s definitely not “theft” to learn from work!

The flip side of this is that you do actually have to be able to lawfully view the material for any of this logic to apply. There is not an unlimited, automatic right to be able to view and learn from all information. You can’t demand free access to copyrighted work just because you want to learn from it. You can buy a copy, use a library, or find it published on the internet, but you still need to have a lawful way to access it in the first place.

So, if a company just pirates all the copyrighted material they can and use it to train a model, that’s still obviously illegal. In addition to the unfair competition issue, that particular model is the direct result of specifically criminal activity, and it’d be totally inappropriate if the company could still make money off it.

Meta did exactly that, because they don’t care about any of this high-minded “what’s actually legal” business. They’re just crooks.

Kate Knibbs, “Meta Secretly Trained Its AI on a Notorious Piracy Database, Newly Unredacted Court Docs Reveal” These newly unredacted documents reveal exchanges between Meta employees unearthed in the discovery process, like a Meta engineer telling a colleague that they hesitated to access LibGen data because “torrenting from a [Meta-owned] corporate laptop doesn’t feel right 😃”. They also allege that internal discussions about using LibGen data were escalated to Meta CEO Mark Zuckerberg (referred to as “MZ” in the memo handed over during discovery) and that Meta’s AI team was “approved to use” the pirated material.

“Meta has treated the so-called ‘public availability’ of shadow datasets as a get-out-of-jail-free card, notwithstanding that internal Meta records show every relevant decision-maker at Meta, up to and including its CEO, Mark Zuckerberg, knew LibGen was ‘a dataset we know to be pirated,’” the plaintiffs allege in this motion.

This is a completely different situation than using works you own or scraping publicly available data from the internet. This is just doing crimes for profit. The model created from pirated data is criminal proceeds, and Meta should absolutely not be permitted to use the ill-gotten assets as part of any further business.

Meta’s behavior here is an extremely relevant case because it’s an explicit example of crossing the line into illegality. By my logic here, Meta had an extraordinarily large amount of data they could have trained on: any data in the public domain, any data published on the open web, and any media they purchased even one copy of. But instead they chose to train using more data than they had any right to access in the first place. Even though I’m arguing that most training should be legal, by engaging in unabashed media piracy to acquire the data in the first place Meta shows a clear example of what violating the limits and engaging in illegal training looks like.

Feature, not a bug

Copyright allowing people to freely learn from creative works makes complete sense because it also maps directly to what copyright is ultimately for.

The point of copyright in the first place is to incentivize development and progress of the arts by offsetting a possible perverse incentive that would stop people from creating new work. Learning from other work and using that knowledge to develop new works is exactly the behavior copyright is designed to encourage. Moreover, when copyright does grant exclusive rights to creators, it only protects tangible creative expressions. It’s not a monopoly right over a vast possibility space of all the work they could theoretically make. So it’s exactly correct that learning is not a reserved right, and letting people view work necessarily allows them to learn from it.

Hinge question: is training copying?

So let’s bring this back around to the main question: whether existing copyright principles let creators restrict AI training.

Training an AI involves processing large volumes of creative material. In the standard scenario where the entity training the model has the right to view that work but no particular license to copy it, is the act of training a copyright violation? The vital question this hinges on is this: is the actual act of training an AI equivalent to copying, or is it more comparable to viewing and analysis? Are companies training on work copying that work (which they do not have the right to do) or reviewing the work (which they do)? If training is copying, then training on this data would be a copyright violation. If not, we’ll have to dig deeper to find a reason model training on unlicensed material could be illegal.

I think the unambiguous answer to this question is that the act of training is viewing and analysis, not copying. There is no particular copy of the work (or any copyrightable elements) stored in the model. While some models are capable of producing work similar to their inputs, this isn’t their intended function, and that ability is instead an effect of their general utility. Models use input work as the subject of analysis, but they only “keep” the understanding created, not the original work.

Training is analysis

Before understanding what training isn’t (copying), it’s important to understand what training is for, on both a technical and practical level.

A surprisingly popular understanding is that generative AI is a database, and constructing an output image is just collaging existing images it looks up on a table. This is completely incorrect. The ways generative AI training actually works is something legitimately parallel to how humans “learn” what things should look like. It’s genuinely incredible technology, and it’s not somehow “buying the hype” to accurately understand the process.

Training is the process of mathematically analyzing data and identifying underlying relationships, then outputting a machine-usable model of information that describes how to use those relationships to generate new outputs that follow the same patterns. The data in the model isn’t copied from the work, it’s the analysis of the work.

This is something even the original complaint in the Andersen v. Stability AI case gets right:

Andersen v. Stability AI Ltd. Complaint The program relies on complicated mathematics, linear algebra, and a series of algorithms and requires powerful computers and computer processing to recognize underlying relationships in the data.

With generative AI, the purpose of models is to use this “understanding” as a tool to create entirely new outputs. The goal is generalization: the ability to “generalize” concepts from inputs and store this information not as a copy, but as vectors that can be combined to form outputs composed not of the words or pixels of training data, but their ideas. Generalization has been one of the main selling points — if not the selling point — of generative AI, ever since the earliest products:

DALL·E: Creating images from text (OpenAI Milestone, 2021)

DALL·E is a 12-billion parameter version of GPT‑3 trained to generate images from text descriptions, using a dataset of text–image pairs. We’ve found that it has a diverse set of capabilities, including creating anthropomorphized versions of animals and objects, combining unrelated concepts in plausible ways, rendering text, and applying transformations to existing images.

…

Combining unrelated concepts

The compositional nature of language allows us to put together concepts to describe both real and imaginary things. We find that DALL·E also has the ability to combine disparate ideas to synthesize objects, some of which are unlikely to exist in the real world. We explore this ability in two instances: transferring qualities from various concepts to animals, and designing products by taking inspiration from unrelated concepts.

While elements of the output like “form”, “technique”, and “style” bear resemblance to their source data, the form and function of the final generated product is up to the user and doesn’t need to resemble any of the training inputs.

Training saves the results of this analysis as a model. Copyright, though, is concerned with the reproduction of works. The compositional elements that training captures, like technique and style, are explicitly un-copyrightable. You can’t copyright non-creative choices: you can’t copyright a style, you can’t copyright a practice, you can’t copyright a technique, you can’t copyright a motif, and you can’t copyright a fact.

This means many elements of copyrighted works are not themselves copyrighted or copyrightable. For example, “cats have four legs and a tail” is a fact that might be encapsulated in art, and an AI might be able to “understand” that well enough to know to compose a depiction of a cat. But creating another picture of a cat isn’t violating any copyright, because even if a copyrighted work was used to convey the information, you can’t reserve an exclusive right over the knowledge of what cats are. The data training captures is an understanding of these un-copyrightable elements.

“Understanding” in tools

What’s fascinating about generative AI, from a technological perspective, is how this modeled understanding of relationships in the data is unlike traditional programming and instead functions like subconscious pattern recognition. The model does not understand the meaning of the patterns, and so doesn’t start with a human-authored description of the subject, nor does it construct an articulated program that can be run to produce a specific kind of output. The model is instead an attempt to capture an unarticulated understanding of what correct forms and patterns “seem like”.

I’m using the word “understanding” here to capture the functionality of the tool, but I don’t mean to imply that it’s conscious or sentient. Machine learning is not a magical thinking machine, but it’s also not a database of examples it copies. It’s a specific approach to solving a particular kind of problem. In the same way scripted languages emulate conscious executive function, machine learning emulates unconscious processes.

In terms of real-life tasks, there’s a type of mental task that’s done “consciously” by executive function, and a type of task that’s done “unconsciously.” Traditional programming is based on creating a machine that executes a program composed of consciously-written instructions, mirroring executive function. Mathematics, organization, logic, etc are things we learn to do consciously with intent, and can describe as a procedure.

But there are also mental tasks people do unconsciously like shape recognition, writing recognition, facial recognition, et cetera. For these, we’re not doing active analysis according to a procedure. There’s some unconscious subsystem that gives our executive consciousness information, but not according to a procedure we consciously understand or can articulate as a procedure a machine could follow.

AI instead tries to emulate these functionalities of the unconscious mind. For machine learning tasks like image recognition, instead of describing a logical procedure for recognizing various objects, the process of training creates a model that can later be used to “intuit” answers that reflect the relationships that were captured in the model. Instead of defining a specific procedure, the relationships identified in training reflect a model of what “correctness” is, and so allows a program to work according to a model never explicitly defined by human statements. When the program runs, the output behavior is primarily driven by the data in the model, which is an “understanding” of the relationships found in correct practice.

That’s why I think that the process of training really is, both mechanically and philosophically, more like human learning than anything else. It’s not quite “learning”, since the computer is a tool and not an actor in its own right, but it’s absolutely parallel to the process of training a subconscious. “Training” to create a “model” is the right description of what’s happening.

Training is not copying

Even if it’s for the purpose of analysis, it’s still critical that training not involve copying and storing the input data, which would be unlicensed reproduction. But training itself isn’t copying or reproduction, on either a technical or practical level. Not only does training not store the original data in the model, the model it generates isn’t designed to reproduce the inputs.

Not storing the original data

First, copies of the training data are not stored in the model at all, not even as thumbnails. Text models don’t have excerpts of works and image models don’t have low-resolution thumbnails or any pixel data at all.

This is such a common misconception that this myth was the argument made by the Stability lawsuit I described in “Naive copying”, that the act of training is literally storage of compressed copies of the inputs:

Andersen v. Stability AI Ltd. Complaint By training Stable Diffusion on the Training Images, Stability caused those images to be stored at and incorporated into Stable Diffusion as compressed copies. Stability made them without the consent of the artists and without compensating any of those artists.

When used to produce images from prompts by its users, Stable Diffusion uses the Training Images to produce seemingly new images through a mathematical software process. These “new” images are based entirely on the Training Images and are derivative works of the particular images Stable Diffusion draws from when assembling a given output. Ultimately, it is merely a complex collage tool. …

All AI Image Products operate in substantially the same way and store and incorporate countless copyrighted images as Training Images. …

Stability did not attempt to negotiate licenses for any of the Training Images. Stability simply took them. Stability has embedded and stored compressed copies of the Training Images within Stable Diffusion.

This description is entirely wrong. While it might be understandable as a naive guess at what’s going on, it’s provably false that this is what’s happening. It’s objectively untrue that the input data is stored in the model. Not only is that data not found in the models themselves, but the general technology is based on published research, and the process of training simply does not involve doing that. It’s baffling that anyone was willing to go on the record as saying this, let alone make it the basis of a major lawsuit.

But even without requiring any knowledge of the process or the ability to inspect the models (both of which we do have), it’s literally impossible for the final model to contain compressed copies of the training images, because the model file simply isn’t big enough. From a data science perspective, we know full artistic works simply cannot be compressed down to one byte and reinflated, no matter how large your data set is. This should align with your intuition, too; you can’t fit huge amounts of data in a tiny space!

Kit Walsh, How We Think About Copyright and AI Art The Stable Diffusion model makes four gigabytes of observations regarding more than five billion images. That means that its model contains less than one byte of information per image analyzed (a byte is just eight bits—a zero or a one). The complaint against Stable Diffusion characterizes this as “compressing” (and thus storing) the training images, but that’s just wrong. With few exceptions, there is no way to recreate the images used in the model based on the facts about them that are stored. Even the tiniest image file contains many thousands of bytes; most will include millions. Mathematically speaking, Stable Diffusion cannot be storing copies …

This is a technical reality, but it also makes intuitive sense that it doesn’t need to store images to work. The model isn’t trying to copy any given work, it’s only storing an understanding of the patterns and relationships between pixels. When an artist is sketching on paper and considering their line quality, that process doesn’t involve thinking through millions of specific memories of individual works. The new work comes from an understanding: information generated from study of the works, but not a memorized copy of any set of specific images.

Not reproducing

The Stable Diffusion lawsuit also makes the accusation that image diffusion is fundamentally a system to reconstruct the input images, and that the model is still effectively a reproduction tool:

Andersen v. Stability AI Ltd. Complaint Diffusion is a way for a machine-learning model to calculate how to reconstruct a copy of its Training Images. For each Training Image, a diffusion model finds the sequence of denoising steps to reconstruct that specific image. Then it stores this sequence of steps. … A diffusion model is then able to reconstruct copies of each Training Image. Furthermore, being able to reconstruct copies of the Training Images is not an incidental side effect. The primary goal of a diffusion model is to reconstruct copies of the training data with maximum accuracy and fidelity to the Training Image. It is meant to be a duplicate.

…

Because a trained diffusion model can produce a copy of any of its Training Images—which could number in the billions—the diffusion model can be considered an alternative way of storing a copy of those images.

If this were the case, it would be a solid argument against generative AI. Even if the model itself doesn’t contain literal copies of input work, it would still be a copyright violation for it to reproduce its inputs (or approximations of them) on-demand. And if the primary purpose of the tool were to make unlicensed copies of copyrighted inputs, that could make training a problem. Even if we can’t show copies being made during training, or analyze the model to find stored copies, if the main thing the tool does is make unlicensed reproductions of existing input works, that’s an issue.

But are any of those accusations actually true? Pretty solidly “no”.

The claim made in the suit is fundamentally wrong on all accounts.

Not only does generative AI work like this in general, this isn’t even how Stable Diffusion works in particular.

From a technical, logical, and philosophical perspective, we know the models don’t have copies of the original data, only information about the relationships between forms. They try to generate new work to match a prompt, and the new work is the product of the prompt, the model, and a random seed.

There’s nothing close to a “make a copy of this specific input image please” button, and if you try to make it do that anyway, it doesn’t work.

When people have tried to demonstrate a reproductive effect in generative AI — even incredibly highly motivated people arguing a case in a court of law — they have been unable to do so. This played out dramatically in the Stability AI lawsuit, where complainants were unable to show cases of output even substantially similar to their copyrighted inputs, and so didn’t even make an allegation that was the case. Instead, they made the argument that there was somehow a derivative work involved even though there was nothing even resembling reproduction, and the judge rightly struck it down:

SARAH ANDERSEN, et al., v. STABILITY AI LTD., et al., ORDER ON MOTIONS TO DISMISS AND STRIKE … I am not convinced that copyright claims based [on] a derivative theory can survive absent ‘substantial similarity’ type allegations. The cases plaintiffs rely on appear to recognize that the alleged infringer’s derivative work must still bear some similarity to the original work or contain the protected elements of the original work.

Carl Franzen, “Stability, Midjourney, Runway hit back in AI art lawsuit” However, the AI video generation company Runway — which collaborated with Stability AI to fund the training of the open-source image generator model Stable Diffusion — has an interesting perspective on this. It notes that simply by including these research papers in their amended complaint, the artists are basically giving up the game — they aren’t showing any examples of Runway making exact copies of their work. Rather, they are relying on third-party ML researchers to state that’s what AI diffusion models are trying to do.

As Runway’s filing puts it: “First, the mere fact that Plaintiffs must rely on these papers to allege that models can “store” training images demonstrates that their theory is meritless, because it shows that Plaintiffs have been unable to elicit any “stored” copies of their own registered works from Stable Diffusion, despite ample opportunities to try. And that is fatal to their claim.”The complaint goes on:“…nowhere do [the artists] allege that they, or anyone else, have been able to elicit replicas of their registered works from Stable Diffusion by entering text prompts. Plaintiffs’ silence on this issue speaks volumes, and by itself defeats their Model Theory.”

The same dynamic played out in another case, this time with complainants unable to demonstrate similarity even with much simpler text examples:

Blake Brittain, “US judge trims AI copyright lawsuit against Meta” The authors sued Meta and Microsoft-backed OpenAI in July. They argued that the companies infringed their copyrights by using their books to train AI language models, and separately said that the models’ output also violates their copyrights.

[U.S. District Judge Vince Chhabria] criticized the second claim on Thursday, casting doubt on the idea that the text generated by Llama copies or resembles their works.

“When I make a query of Llama, I’m not asking for a copy of Sarah Silverman’s book – I’m not even asking for an excerpt,” Chhabria said.

The authors also argued that Llama itself is an infringing work. Chhabria said the theory “would have to mean that if you put the Llama language model next to Sarah Silverman’s book, you would say they’re similar.”

…

The judge said he would dismiss most of the claims with leave to amend, and that he would dismiss them again if the authors failed to argue that Llama’s output was substantially similar to their works.

It’s also not true that generated outputs are “mosaics”, collages”, or snippets of existing artwork interpolated together. The tool fundamentally doesn’t work like that; it neither reproduces and composes image segments nor interpolates image chunks. Asserting that generative AI is a “collage” tool isn’t even reductive, it’s entirely wrong at all levels.

Memorization and Overfitting

I have to take time away from my main argument here to make an important caveat, which is that it’s not true to categorically say generative AI is truly incapable of reproducing any of the work it was trained on. This is true from a data science perspective (since the domain of the training data overlaps with the domain of possible outputs), but it’s also practically possible to use a model to generate images that resemble its inputs, under specific conditions.

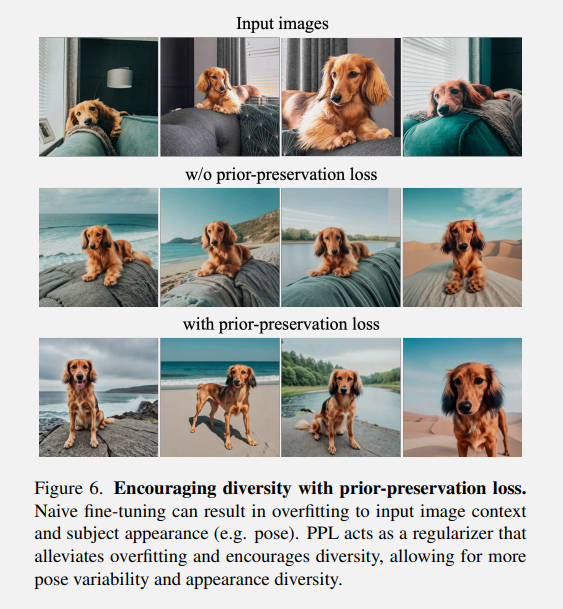

In the field of generative AI research, if even 1%-2% of the outputs of a generative model are similar to any of the model’s inputs, that’s called overfitting, and it’s a bug. Overfitting is waste, and prevents these tools from being able to do their job.

“Memorization” is a similar bug that’s describes exactly what it sounds like: when an AI model is able to reproduce something very close to one of its inputs. Overwhelmingly, memorization is caused by bad training data that includes multiple copies of the same work. Since famous works of art are often duplicated in data sets of publicly available images, the model “knows” them very well and is able to reproduce them with a high level of fidelity if prompted:

Original Mona Lisa on left, Midjourney v4, “The Mona Lisa by Leonardo da Vinci” on right

So far in this article I’ve been discussing generative AI at a very high level. The actual frequency of overfitting and “input memorization” varies significantly depending on the dataset, training methodology, and other technical factors specific to individual products.

By running “attacks” on Stable Diffusion, models can be tricked into reproducing some of its input images to a reasonable degree of recognizability. Carlini, N., Hayes, J., Nasr, M., Jagielski, M., Sehwag, V., Tramèr, F., Balle, B., Ippolito, D., & Wallace, E. (2023). Extracting Training Data from Diffusion Models was one study in memorization. Researchers trained their own Stable Diffusion model on the CIFAR-10 dataset of publicly-available images. Given full access to the original data and their trained model, they attempted to generate image thumbnails that were significantly similar to images found in the input data. They were able to show “memorization” of only 1,280 images, or 2.5% of the training data.

I think, once again, this is very parallel to the human process. If you asked someone to draw a specific piece they’ve seen, they could probably approximate it around 2% of the time.

The case where a very generic prompt is able to produce a relatively specific work seems suspicious, but — again — makes sense when compared to a human. If you asked a human artist for something extremely tightly tied to one kind of work like “Italian video game plumber” they’d probably make the same associations you do, and draw something related to Mario unless you told them not to.

Since the entire purpose of generative models is to be able to generate entirely new output, it’s very important to make sure individual input images are dependent mostly on the prompt given to the generator and not any particular images in the training data. Generative AI needs to have the broadest possible possibility space, and so significant amounts of research go towards that goal:

This isn’t a cover-your-ass measure to make sure a service isn’t accidentally reproducing copyrighted materials (like Google Books, which stores full copies of books but is careful not to expose the underlying data to the public). The entire value of generative AI is that its outputs are new and not redundant. Accidentally outputting images that are even remotely similar to the inputs is poor performance for the product itself.

In this way, AI training is once again parallel to human learning. Generative AI and human work have the same criteria for success. As an artist learning on material, you don’t want the input images to be closely mimicked in the outputs. You don’t want your style or pose choices to be dependent on specifics from your example material. You want to learn how to make art, and then you should be able to make anything.

Don’t expand copyright to do this

So, we can rule out AI training as being a copyright violation at this point. Training only requires the same ability to view and analyze work people already have. The training itself doesn’t involve “compressing” or making a copy of the work, and it doesn’t result in a tool that acts as a database that will reproduce the original inputs on demand. So just the act of training a model isn’t a copyright violation, even if the material used was copyrighted.

But is this the wrong outcome? Copyright isn’t a natural law that can only be understood and worked within; it’s an institution humans have created in order to meet specific policy goals. So should copyright powers be expanded to give creators and rightsholders a mechanism to prevent AI training on their works unless they license those rights? Can you somehow split the right to view the material and the right to learn from the material? Or could you isolate AI training as a case where the rates could be separate?

The answer to all these questions is no. You can’t (and shouldn’t) expand copyright to limit how people can train on the material, no matter what tools are involved.

Creative work should not be considered a “derivative work” of every inspiring source and every work that their author used to develop their skills. And there’s not a sound way to make an argument for heavy creative restrictions that only “sticks” to generative AI, and not human actors.

It’s against sound philosophical principles — including copyright’s — to try to attack tools and not specific objectionable actions. The applications of AI that are specifically offensive (i.e., plagiarism) are applications. Trying to go after the tools early is overaggressive enforcement that short-circuits due process in a way that prevents huge amounts of behavior that doesn’t represent any kind of legitimate offense against artists. There’s also not a clear way to cut a line between training and human learning.

AI is a general-purpose tool and offenses are downstream

First, generative AI is a general-purpose tool. It’s possible for people to intentionally use it in objectionable ways (plagiarism, replication, etc.), but the vast majority of its uses and outputs don’t constitute any sort of legitimate offense against anyone. The argument against training is that it creates a model that could be misused in the future, but it’s completely inappropriate to use copyright legislation to prevent the creation of a tool in the first place. Law has no business banning general-purpose tools just because they could potentially* be used later in infringing ways.

Generative AI is a tool, and has to be used by a human agent to produce anything other than noise. There’s agreement on this point across the spectrum, including the very wrong papers arguing for expansion of copyright to cover learning rights:

Jiang, H. H., Brown, L., Cheng, J., Khan, M., Gupta, A., Workman, D., Hanna, A., Flowers, J., & Gebru, T. (2023). AI Art and its Impact on Artists. Proceedings of the 2023 AAAI/ACM Conference on AI, Ethics, and Society, 363–374. In conclusion, image generators are not artists: they require human aims and purposes to direct their “production” or “reproduction,” and it is these human aims and purposes that shape the directions to which their outputs are produced.

The tools used don’t single-handedly determine if a particular action constitutes copyright infringement. Whether creating a new work constitutes copyright infringement (or even plagiarism more generally) is determined by the nature of the new work, not the method of its creation. If a tool is generally useful, you can’t argue that using that particular tool is evidence of foul play. It’s the play that can be foul, and that comes from the person using the tool. The evaluation of the work depends on the work itself.

Imagine the scenario where someone opens an image in Paint, changes it slightly, and passes the altered copy off as their original work. That’s copyright infringement because the output is an infringing copy and plagiarism because it’s being falsely presented as original authorship. The fact that Paint was used doesn’t mean Paint is inherently nefarious or that any other work made with Paint should be presumed to be nefarious.

The user was responsible for the direction and output of the tool. Neither the software nor its vendor participated; the user who actively used the tool towards a specific goal was the only relevant agent. The fact that the computer internally copies bytes from disk to RAM to disk doesn’t mean computers, disks, or RAM are inherently evil either. Tools just make people effective, and a person used that ability to commit orthogonal offenses.

Plagiarism and copyright infringement aren’t the only harms generative AI can be used to inflict on people. “Invasive style mimicry” can be a component of all sorts of horrible abuse:

Jiang, H. H., Brown, L., Cheng, J., Khan, M., Gupta, A., Workman, D., Hanna, A., Flowers, J., & Gebru, T. (2023). AI Art and its Impact on Artists. Proceedings of the 2023 AAAI/ACM Conference on AI, Ethics, and Society, 363–374. This type of invasive style mimicry can have more severe consequences if an artist’s style is mimicked for nefarious purposes such as harassment, hate speech and genocide denial. In her New York Times Op-ed, artist Sarah Andersen writes about how even before the advent of image generators people edited her work “to reflect violently racist messages advocating genocide and Holocaust denial, complete with swastikas and the introduction of people getting pushed into ovens. The images proliferated online, with sites like Twitter and Reddit rarely taking them down.” She adds that “Through the bombardment of my social media with these images, the alt-right created a shadow version of me, a version that advocated neo-Nazi ideology… I received outraged messages and had to contact my publisher to make my stance against this ultraclear.” She underscores how this issue is exacerbated by the advent of image generators, writing “The notion that someone could type my name into a generator and produce an image in my style immediately disturbed me… I felt violated.”

But these aren’t issues uniquely enabled by AI, and harsh restrictions on AI won’t foil Nazism.

Plagiarism, forgery, and other forms of harmful mimicry are not novel dynamics. Generative AI does not introduce these problems into a culture that hasn’t already been dealing with them. These are categories of violations that aren’t coupled to specific tools, but are things people do using whatever means are available.

The same logic applies to everything. Using copy-paste while editing a document doesn’t mean the final product doesn’t represent your original work, even though plagiarism is one of the things copy-paste can do. Tracing and reference images can be used for plagiarism, but the tools in use don’t determine the function of the product.

Learning isn’t theft. If it’s a machine for doing something that is not theft, it’s not a theft machine. It’s just a machine that humans can use to do the same things they were already doing.

Short-circuiting process

Going after the tools early to enforce/prevent copies is an attempt to short-circuit due process.

The idea that we should structure technology such that people are mechanically unable to do a particular objectionable thing is a familiar perversion of enforcement. This is a topic I want to write on later in more depth, but as it relates to learning rights, this is a pretty clear attempt to aggressively prevent whole categories of behavior by preemptively disabling people from a whole category of behavior.

Media companies frequently make the argument that an entire category of tools (from VHS to hard drives) needs to be penalized or banned entirely just because it’s possible to use the tool in a way that infringes copyright. Arguing to prevent the training of generative AI in the first place is exactly the same cheat: trying to criminalize a tool instead of adjudicating specific violations as appropriate.

Because no one has been able to show that models are actually infringing works, anti-AI lawsuits are reduced to trying to make the act of training illegal. This is a dangerously wrong approach. The actual question copyright is concerned with is whether a specific work infringes on a reserved right. This is a question you can only effectively ask after a potentially infringing work is produced, and in order to evaluate the claim you have to examine the work in question.

This is obviously not what corporations with “IP assets” would prefer. It would be much safer for them if no potentially infringing work could be created in the first place. If it’s impossible to make new art at all, not only do the rightsholders not have to make a specific claim and argue a specific case, they don’t risk any “damage” being done by circulation of an infringing work before they can catch it.

It makes complete sense that this is what they’d prefer, but total prevention satisfies that party at the expense of everyone else (and creativity as a whole), so it’s the job of a functional system to not accommodate it. The whole point of copyright needs to be encouraging the creation of new works, not giving rightsholders whatever conveniences they can think to ask for. Overaggressive enforcement that prevents whole categories of work from being produced in the first place needs to be completely off the table.

Going after tools instead of individual works is an attempt to short-circuit the system. People creating work and being challenged if there’s a valid challenge to make is the only way this can reasonably be managed. If tools are banned and copyright expansionists are successful in preventing vast spaces of completely legitimate, non-infringing works from being created in the first place, that’s a disaster. In effect those works are all being banned without anything approaching due process. Artists have a right to defend themselves against accusations of copyright infringement, but if whole categories of work are guilty until proven innocent, the work can’t be created in the first place, and the opportunity for due process people are owed is implicitly smothered.

No clear line to cut against “automation”

People objecting to training generative AI are objecting to a kind of learning, but they don’t have that same objection when people do the same thing. As I’ve said, I don’t think any reasonable person actually objects to humans learning from existing work they have access to. No, the objection to model training is tied to the “automatedness” of the training and the “ownability” of the models. Humans doing functionally the same thing (but slower) isn’t an issue.

So, if the problem is how automated or synthetic the tool is, is that somewhere we can draw a policy line? Is the right approach to say only humans can learn freely, and an automated system needs an explicit license to do the equivalent training?

I think this is another direction that makes some sense as a first thought, but quickly breaks down when taken to its logical conclusions. There simply isn’t a meaningful way to distinguish between a “tool-assisted” process and a “natural” process. Any requirement trying to limit AI training on the basis of its actual function of learning from work would necessarily limit human learning as well. And not in a way that can be solved by just writing down “no it doesn’t” as part of the policy!

Remember, AI is a tool, not an actor. There’s no sentient AI wanting to learn how to make art, only people building art-producing tools. So if you want to make a distinction here, it’s not between a person-actor and a machine-actor, it’s between a person with a tool and a person without a tool.

This is a pet issue of mine. I am convinced that trying to draw a clean line between “people” and “technology” is a disastrously bad idea, especially if that distinction is meant to be a load-bearing part of policy. People aren’t separable from technology. The fact that we use tools is a fundamental part of our intelligence and sapience. Every person is a will enacting itself on the world through various technical measures. If you don’t let a builder use a hammer or a painter use a brush, you’re crippling them just as if you’d disabled their arms. And — looking in the other direction — the body is a machine we use the same way as we use any tool. We use technology and tools as prosthesis that fundamentally extend human function, which is a good thing.

This “real person” distraction is a common stumbling point in discussions about things like accessibility. The goal is not to determine some “standard human” with a fixed set of capabilities and enforce that standard on people. The goal isn’t just to “elevate” the “disabled” to some minimum viable standard, and it’s certainly not to reduce the function of over-performers until everyone fits the same mold.3 Access and function are goods in and of themselves, and it’s worthwhile to extend both.

AI is fundamentally the same kind of tool we expect people to use regularly, but a degree more “advanced” than our expectations. The people arguing that AI is anti-art aren’t arguing that the correct state of affairs is a technological jihad, they’re wanting to return to “good technology”, like Blender. But that’s no basis for a categorical distinction.

Sun Mar 30 19:53:27 +0000 2025you wanna know what kind of tech ACTUALLY “democratizes art”? MSPaint, iMovie, RPGMaker, Garage Band, VLC Player, Godot, Twine, Audacity, Blender, archive dot org, GitHub, aseprite, Windows Movie Maker, GIMP,

If you’re trying to divide technology into categories of “good tools” and “bad tools”, you need a clear categorical distinction. But what is the criteria that makes generative AI uniquely bad? There doesn’t appear to be one. It’s obviously not just that generative AI is software. It also can’t be that generative AI is “theft-based”, because it obviously isn’t. It’s performing the same dynamic of learning that we want to see, but using software to do it. And we know “using software to do it” doesn’t turn a good thing bad. And it’s obviously absurd to say we should stop building new tools at some arbitrary point, and only techniques that were already invented and established are valid to use.

Trying to find separate criteria that happens to map onto the result that makes sense to you, at the moment, is a dangerous mistake. (A “policy hack”, which is another topic I plan to write on later....) No, if you’re going to try to regulate a specific dynamic (in this case, learning) you need to actually regulate the dynamic in question in a clear, internally-consistent way.

Consequence of new learning rights enforcement

There’s also a bigger-picture reason the learning rights approach is bad, even for the people still convinced copyright law should be expanded to include learning rights: doing this would not accomplish the things they want to accomplish, and instead make the world worse for everyone. And, importantly, it won’t eliminate the technology or keep corporations from abusing artist labor, which are the outcomes the people pushing for change want.

This is a common problem with reactionary movements. There’s an earnest, almost panicked energy that there’s a need to “get something done”, but if that energy goes to the wrong place, you’re just doing unnecessary harm.

The reason I care about the “philosophy of copyright” or whatever isn’t to invent a reason to let harm continue to be done unabated. Systems matter because systems affect reality, and understanding the mechanics is necessary to keep a reactionary response from doing more harm. Even if you want to “cheat” and get something done right now, the “break-glass” workarounds just aren’t pragmatic.

Expanding copyright disadvantages individuals

People are using the threat of AI to argue for new copyright expansions in order to protect artists from exploitation. But this misunderstands a fundamental dynamic, which is that expanding copyright in general is bad for artists because of the way the system is weighted in favor of corporations against individuals.

All the systems of power involved in IP enforcement that currently exist are heavily, heavily weighted in the favor of large corporations. The most basic example of this is that going through a legally-adjudicated copyright dispute in the courts can be made into a battle of attrition, and so the companies that can afford extensive legal expenses can simply outspend individuals in disputes. This makes any expansion of copyright automatically benefit corporations over small artists, just procedurally. Massively strengthening copyright enforcement power is not going to help the artists whose work is being used when the powers being enforced are already slanted to disadvantage those artists.

2024-11-28T07:25:32.729ZTrying to enclose and commodify information so that only people who can pay a competitive market rate won’t somehow disadvantage the corporations. Setting up a system that requires you to be optimally efficient at converting information to US dollars is not going to give the common man a leg up.

When the question is very hard, and all the general systems of power are pointed in the wrong direction, “We have to take immediate action to fix this!” is a wrong and very dangerous response. Anti-AI artists are supporting copyright as the thing it’s supposed to be, but the power they try to give it goes to a system of power that works against them instead.

Artists compelled to relinquish rights to gatekeepers

Creating a learning right would create a new licensable right, and so seems like this would create a new valuable asset creators could own. But think about what happens to the rights creators already have: huge media companies already own most of “the rights” to work, because they’re able to demand artists relinquish them in order to participate in the system at all. This is the Chokepoint Capitalism thesis.

Artists are already compelled to assign platforms and publishers rights over their creative work as a condition for employment or distribution. If the “learning rights” to your work suddenly become a licensable asset, that doesn’t actually make you richer. That just creates another right companies like Penguin Random House can demand themselves as part of a publishing contract, and then resell to AI companies without you ever seeing a dime from it.

In anticipation of learning rights becoming a real thing, companies like Meta and Adobe are already using whatever dirty tricks they can invent to strip individual creators of those rights and stockpile them for corporate profit.

This dynamic has already been covered thoroughly, to the point where I can cover the topic completely by simply quoting existing work:

Katharine Trendacosta and Cory Doctorow, “AI Art Generators and the Online Image Market” Requiring a person using an AI generator to get a license from everyone who has rights in an image in the training data set is unlikely to eliminate this kind of technology. Rather, it will have the perverse effect of limiting this technology development to the very largest companies, who can assemble a data set by compelling their workers to assign the “training right” as a condition of employment or content creation.

… Creative labor markets are intensely concentrated: a small number of companies—including Getty—commission millions of works every year from working creators. These companies already enjoy tremendous bargaining power, which means they can subject artists to standard, non-negotiable terms that give the firms too much control, for too little compensation.

If the right to train a model is contingent on a copyright holder’s permission, then these very large firms could simply amend their boilerplate contracts to require creators to sign away their model-training rights as a condition of doing business. That’s what game companies that employ legions of voice-actors are doing, requiring voice actors to begin every session by recording themselves waiving any right to control whether a model can be trained from their voices.

If large firms like Getty win the right to control model training, they could simply acquire the training rights to any creative worker hoping to do business with them. And since Getty’s largest single expense is the fees it pays to creative workers—fees that it wouldn’t owe in the event that it could use a model to substitute for its workers’ images—it has a powerful incentive to produce a high-quality model to replace those workers.

This would result in the worst of all worlds: the companies that today have cornered the market for creative labor could use AI models to replace their workers, while the individuals who rarely—or never—have cause to commission a creative work would be barred from using AI tools to express themselves.

This would let the handful of firms that pay creative workers for illustration—like the duopoly that controls nearly all comic book creation, or the monopoly that controls the majority of role-playing games—require illustrators to sign away their model-training rights, and replace their paid illustrators with models. Giant corporations wouldn’t have to pay creators—and the GM at your weekly gaming session couldn’t use an AI model to make a visual aid for a key encounter, nor could a kid make their own comic book using text prompts.

Cory Doctorow, Everything Made By an AI Is In the Public Domain Giving more copyright to a creative worker under those circumstances is like giving your bullied schoolkid extra lunch money. It doesn’t matter how much lunch money you give your kid — the bullies are just going to take it.

In those circumstances, giving your kid extra lunch money is just an indirect way of giving the bullies more money. … But the individual creative worker who bargains with Disney-ABC-Muppets-Pixar-Marvel-Lucasfilm-Fox is not in a situation comparable to, say, Coca-Cola renewing its sponsorship deal for Disneyland. For an individual worker, the bargain goes like this: “We’ll take everything we can, and give you as little as we can get away with, and maybe we won’t even pay you that.”

…

Every expansion of copyright over the past forty years — the expansions that made entertainment giants richer as artists got poorer — was enacted in the name of “protecting artists.”The five publishers, four studios and three record labels know that they are unsympathetic figures when they lobby Congress for more exclusive rights (doubly so right now, after their mustache-twirling denunciations of creative workers picketing outside their gates). The only way they could successfully lobby for another expansion on copyright, an exclusive right to train a model, is by claiming they’re doing it for us — for creative workers. But they hate us. They don’t want to pay us, ever. The only reason they’d lobby for that new AI training right is because they believe — correctly — that they can force us to sign it over to them. The bullies want your kid to get as much lunch money as possible.

Andrew Albanese, “Authors Join the Brewing Legal Battle Over AI” But a permissions-based licensing solution for written works seems unlikely, lawyers told PW. And more to the point, even if such a system somehow came to pass there are questions about whether it would sufficiently address the potentially massive issues associated with the emergence of generative AI.

“AI could really devastate a certain subset of the creative economy, but I don’t think licensing is the way to prevent that,” said Brandon Butler, intellectual property and licensing director at the University of Virginia Library. “Whatever pennies that would flow to somebody from this kind of a license is not going to come close to making up for the disruption that could happen here. And it could put fetters on the development of AI that may be undesirable from a policy point of view.” Butler said AI presents a “creative policy problem” that will likely require a broader approach.

But even if artists could realistically keep the rights to their own work, there are other obvious problems with trying to extend copyright such that all work is a “derivative” of the resources used to train the artists.

Monopolies prevent future art

A learning right in particular would be a massive hand-out to media companies like Adobe or stock photo companies who own licenses over vast libraries of images. If people need to license the right to learn from any work in that data set, those companies suddenly have strong grounds to make an argument that almost any new art was derived from art they have exclusive rights over. These companies already have a strong incentive to try to prevent any new competition from being created, so giving them a tool to do exactly that would be disastrous for art.

This would effectively stifle independent artists from creating any new future work. A corporation with a content library can take any work from an individual artist, find the closest work in the library of their own work, and accuse the targeted work of being a product of “unlicensed learning”. An individual artist without a “content library” to draw from would be unable to show that any new work didn’t infringe on this nebulous right. This would give media conglomerates excessive power over artists: they could extort artists for payment or use the threat of a protracted legal battle to selectively censor material they deemed harmful to their own financial interests.

This would exacerbate all the worst problems in the current media ecosystem. Creative industries would necessarily consolidate around a few powerful rightsholder conglomerates, and new artists would face insurmountable barriers to entry. Even without looming threats of fascism and dystopian control, consolidation would lead (as it does) to sanitization, fewer perspectives, and a less pluralistic culture. Much, much more art would necessarily become a corporate output, censored to whatever standards that might require. This might not effectively “destroy art”, but since corporations would have vast power over cases they cared about, it would un-democratize art where it mattered.

And even before the environment got as drastic as that, one obvious thing a learning right does is destroy fan work. Since being able to draw a character or environment is obvious evidence that you learned how to do so from the original work, media properties would have an airtight case that any fan works or parody that references their IP is prima facie evidence of unlicensed training on the material. Even in cases where the fanwork itself isn’t infringing any copyright, this work would be evidence of illegal and unlicensed training on material. This would create a back-door way for media companies to control depictions of their own properties, and yet again extort or censor independent artists.

Not enforceable without invasive DRM on almost all information

Meanwhile, even as an IP regime that enforces learning rights makes artists poorer, it makes digital life hell.

Because the model isn’t copying the work, you can’t reliably determine what work a model was trained on just by examining the model. So in order to enforce a learning right, you have to prevent training in the first place. And to do that, you need chain-of-custody DRM on basically all information.

I would love for this to be the absurd hyperbolic speculation it sounds like, but the IP ghouls are already salivating over the idea. The Adobe/Microsoft Content Provenance and Authenticity (C2PA) campaign is a topic for another essay entirely, but it’s bleak. And Adobe and StabilityAI are already pushing the senate to mandate it.

Astroturfing and reinforced error

Karla Ortiz locking arms with Adobe to petition Congress to expand copyright is a reminder that this is another example of reinforced error.

Tue Aug 13 21:05:14 +0000 2024huge day for maximizing corporate greed and making it impossible to create art freely without deep pockets and massive IP centralization. thanks karla! you're a piece of shit.

Pushes for copyright expansion have always benefited corporations at the expense of artists, but that’s a tough sell. The IP monopolists — the Adobes, the Disneys — need to sell copyright expansion as a measure that “protects artists”, even though it doesn’t.

So, predictably, the “anti-AI” learning rights campaign is the same familiar megacorporations and lobbying groups baiting in and publicly platforming artists, all while arguing for actual policy proposals that enrich themselves at the artists’ expense.

Look behind any door and you’ll see it.

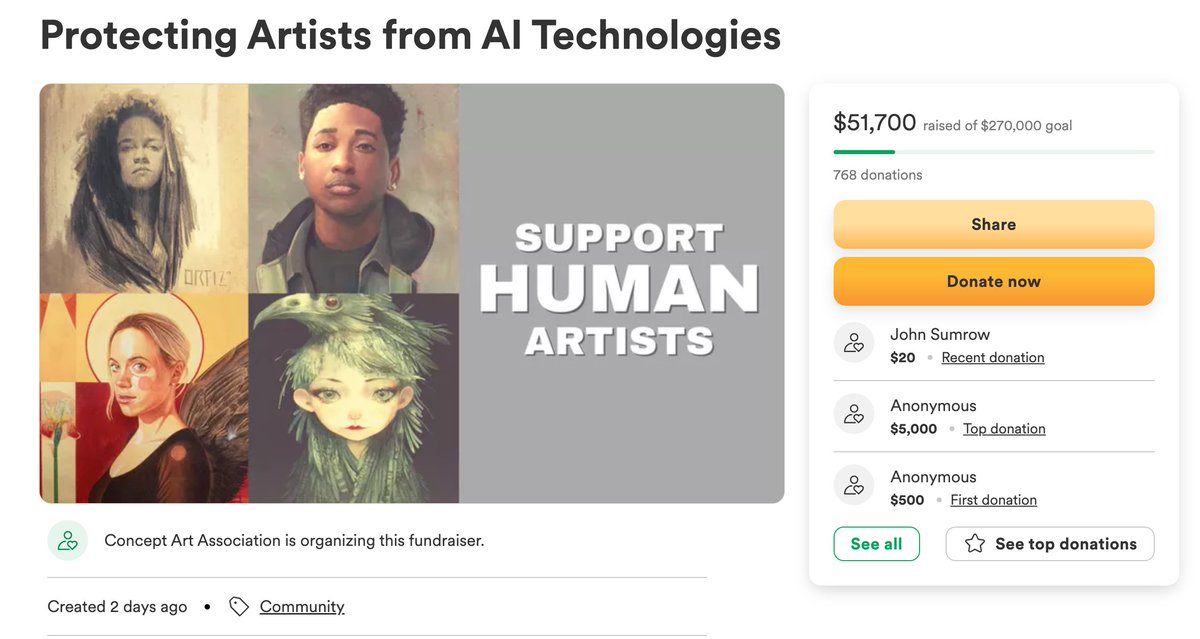

Fri Dec 16 00:47:39 +0000 2022The Concept Art Association is raising money to hire a lobbyist to take the fight against AI image generators to DC. This is the most solid plan we have yet, support below.

The “concept art association” launching a GoFundMe grassroots campaign to support human artists? No, it’s just Karla Ortiz again, this time buying the already-notorious Copyright Alliance a new D.C. lobbyist.

The “Fairly Trained” group proposes to “respect creators’ rights” by coming up with some sort of “certification criteria.” Who’s behind this, you wonder? It’s the same handful of companies who artists are rightfully trying to defend themselves against:

Fairly Trained launches certification for generative AI models that respect creators’ rights — Fairly Trained We’re pleased that a number of organizations and companies have expressed support for Fairly Trained: the Association of American Publishers, the Association of Independent Music Publishers, Concord, Pro Sound Effects, and Universal Music Group.

The IP coalition has always been “corporations, and a rotation of reactionary artists they tricked”, and this issue is no exception.

Identifying the labor problem

When there’s a legitimate problem to be addressed, ruling out one approach doesn’t mean you’re done with the work; it means you haven’t even identified the work that needs to be done yet. So if copyright expansion isn’t the answer, what’s the right way to address the concern?

Let’s look at that original complaint one more time:

When a corporation trains generative AI, they have unfairly used other people’s work without consent or compensation to create a new product they own. Worse, the new product directly competes with the original workers. Since the corporations didn’t own the original material and weren’t granted any specific rights to use it for training, they did not have the right to train with it. When the work was published, there was no expectation it would be used like this, as the technology didn’t exist and people did not even consider “training” as a possibility. Ultimately, the material is copyrighted, and this action violates the authors’ copyright.

Fundamentally, the complaint here isn’t about copyright. What’s being (rightfully!) objected to is a new kind of labor issue.

Corporations unfairly competing with workers: labor issue. Use of new technology to displace the workers who enabled it: labor issue. Using new methods to extract additional value from work without compensation: labor issue.

AI threatens to put creative workers out of a job, and make the world a worse place as it does so:

Xe Iaso, Soylent Green is people My livelihood is made by thinking really hard about something and then rending a chunk of my soul out to the public. If I can’t do that anymore because a machine that doesn’t need to sleep, eat, pay rent, have a life, get sick, or have a family can do it 80% as good as I can for 20% of the cost, what the hell am I supposed to do if I want to eat?

Building highly profitable new tools without compensation is simply unfair:

AG Statement on Writers’ Lawsuits Against OpenAI - The Authors Guild Using books and other copyrighted works to build highly profitable generative AI technologies without the consent or compensation of the authors of those works is blatantly unfair

Corporations are entirely willing to be “disrespectful” in the way they use available labor without consent and compensation, and are doing so in a way that’s entirely willing to harm workers: