or, the many people who said movies like Coyote v. Acme that were killed for a tax write-off should be forced into the public domain were right, and here’s why

Copyright is busted, now what?🔗

A healthy system of creative rights, including a balanced form of copyright, is a reciprocal arrangement between creators, consumers, and the commons. Creators are granted some temporary exclusive rights by the government over qualifying intellectual work in order to incentivize creativity. These privileges are granted in exchange for creating valuable new information — the existence of which is a contribution to the public good — and for providing it in such a way that others will be able to build on it in the future. It’s an incentive for providing a specific social good, one which the market alone might not reward otherwise. Fortunately, this is actually how US copyright was designed; see You’ve Never Seen Copyright.

The takeaway from that, though, is not just that there’s a fair version of copyright, but that copyright must look like that fair model. The fact that such a thing as “good copyright” exists as a sound philosophy is not a broad defense of the word “copyright” itself, it’s an imperative requirement for the legitimacy of any system of power that claims to enforce copyright. The soundness of the philosophy doesn’t legitimate the system of power that shares its name, it damns it for failing its requirements.

When they invoke the philosophy of copyright to justify thuggery, it matters that they’re wrong.

The requirements for reciprocity intrinsic in copyright are how the system must work, but it’s not what actually happens today. In practice, corporations regularly violate the fundamental principles of creative rights — both in letter and in spirit — and use copyright protections to profit without showing the required reciprocity.

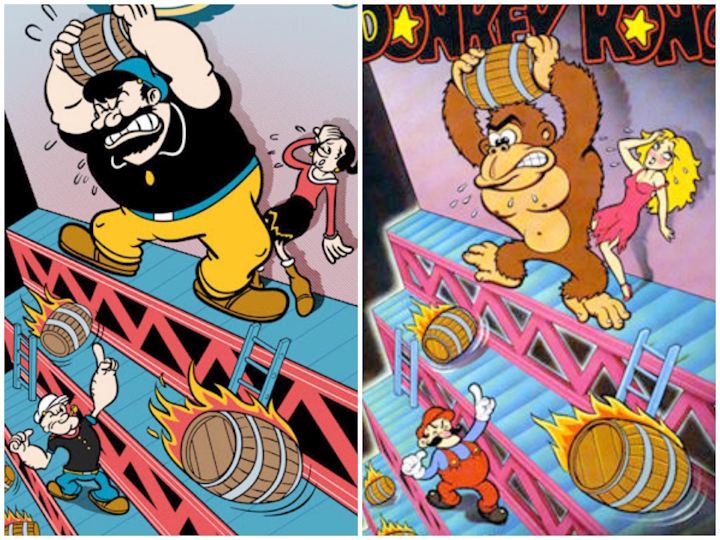

I can’t possibly list all the stories of what these violations look like. Seriously, just the thought of me having to give a representative sample of companies abusing IP law made me dread writing this series, it’s such a prolific problem. But I have shown a sample: Nintendo using copyright to kill new creative work, Apple using trademarks to keep competitors from conducting trade at all, book publishers trying to destroy the idea of buying and selling books… they’re all examples of how companies do everything they possibly can to get out of fulfilling their side of the bargain.

Case studies are fun, but just listing out a bunch of horrors isn’t what I set out to do; that’s just groundwork for thinking about the problem. What’s important is that they’re a representative sample of a kind of behavior. With all that established, you can read this with the knowledge that yes, they violate the purpose of the law as written and yes, violations are so regular they seem to define the practice.

So what does it all add up to?

Here’s what I say: If you want out of the deal, so be it. When someone won’t participate constructively — if they don’t work in good faith, or at least begrudgingly accept the limits the system of copyright puts on them — we stop respecting their claim to special privileges within it as legitimate, and understand it as the double-dealing overreach it is.

As self-evident as it sounds when I say it out loud, this argument is my nuclear option. This is what I would have to say if it ever got this bad; if, between the two of them, the courts and the corps ever broke the system beyond my last bit of tolerance. And I’ll be damned if they haven’t done just that.

Legitimacy🔗

In You’ve Never Seen Copyright, I talked about how the word “copyright” can refer to two very different things: either a philosophical basis that justifies copyright as a legal doctrine, or the system of power that describes how copyright is actually enforced, what enforcement looks like, and who it benefits.

But the fact that the power structure has diverged from the original philosophical intent doesn’t just create a communication issue. Yes, it becomes increasingly unclear what people who say “copyright” are talking about, but the legitimacy of the power structure depends entirely on being an implementation of a sound legal doctrine.

Copyright Abusers Lost Their Claim

Copyright Abusers Lost Their Claim

this is a real graphic Netflix made!

this is a real graphic Netflix made! So you want to write an AI art license

So you want to write an AI art license

Trouble a-brewin' at Redbubble

Trouble a-brewin' at Redbubble