I keep seeing people make this error, especially in social media discourse. Somebody wants to “use” something. Except obviously, it’s not theirs, and so it’s absurd for them to make that demand, right?

Quick examples

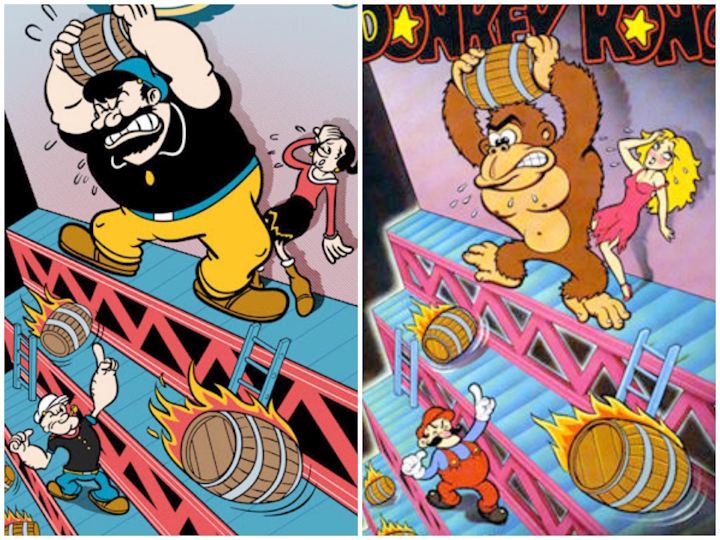

I’m not trying to pick on this person at all: they’re not a twitter main character, they’re not expressing an unusual opinion here, they seem completely nice and cool. But I think this cartoon they drew does a good job of capturing this sort of argument-interaction, which I’ve seen a lot:

Sun Sep 22 22:20:02 +0000 2024???

I’ve also seen the exact inverse of this: people getting upset at artists because once the work is “out there” anyone should be able to “use” it. (But I don’t have a cartoon of this.)

There is an extremely specific error being made in both cases here, and if you can learn to spot it, you can save yourself some grief. What misuse is being objected to? What are the rights to “certain things” being claimed?

The problem is that “use” is an extremely ambiguous word that can mean anything from “study” to “pirate” to “copy and resell”. It can also cover particularly sensitive cases, like creating pornography or editing it to make a political argument.

But everything people do is “using” something. By itself, “use” is not a meaningful category or designation. Say you buy a song — listening to it, sampling it, sharing it, performing it, discussing it, and using it in a video are all “uses”, but the conversations about whether each is appropriate or not are extremely distinct. If you have an objection, it matters a lot what specific use you’re talking about.

But if you’re not specific, there are unlimited combinations of “uses” you could be talking about, and you could mean any of them. And when people respond, they could be responding to any of those interpretations. There’s no coherent argument in any sweeping statement about “use”; the only things being communicated are frustration and a team-sports-style siding with either “artists” or “consumers” (which is a terrible distinction to make!).

Formal logic

This is not a new problem. This is the Fallacy of Equivocation, which is a subcategory of Fallacies of Ambiguity. This is when a word (in this case, “use”) has more than one meaning, and an argument uses the word in such a way that the entire position and its validity hinge on which definition the reader assumes.

The example of this that always comes to my mind first is “respect”, because this one tumblr post from 2015 said it so well:

flyingpurplepizzaeater Sometimes people use “respect” to mean “treating someone like a person” and sometimes they use “respect” to mean “treating someone like an authority”

and sometimes people who are used to being treated like an authority say “if you won’t respect me I won’t respect you” and they mean “if you won’t treat me like an authority I won’t treat you like a person”

and they think they’re being fair but they aren’t, and it’s not okay.

See, here the “argument” relies on implying a false symmetry between two clauses that use the same word but with totally different meanings. And, in disambiguating the word, the problem becomes obvious.

Short-form social media really exacerbates the equivocation problem by encouraging people to be concise, which leads to accidental ambiguity. But social media also encourages people to take offense at someone else being wrong as the beginning of a “conversation”, which encourages people to use whatever definition of other people’s words makes them the wrongest.

Copyright examples

Since I’m already aware that copyright is a special interest of mine, I try to avoid falling into the trap of modeling everything in terms of copyright by default, Boss Baby style. But this is literally the case of a debate over who has the “right” to various “uses” of things that are usually intangible ideas, so I think it’s unavoidably copyright time again.

The ambiguous "use"

The ambiguous "use"

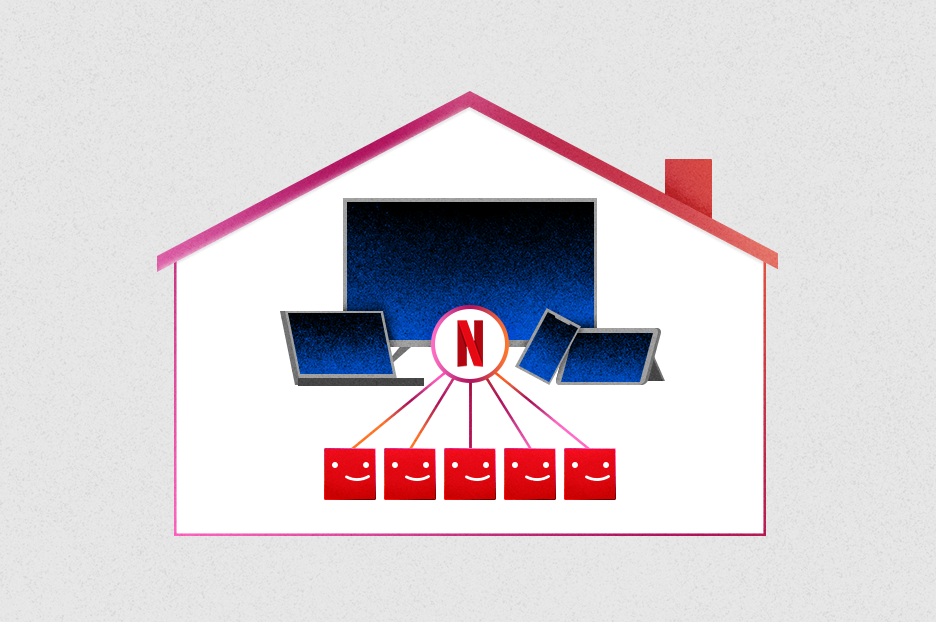

this is a real graphic Netflix made!

this is a real graphic Netflix made!