Pico-8 needs constants

The pico-8 fantasy console runs a modified version of lua that imposes limits on how large a cartridge can be. There is a maximum size in bytes, but also a maximum count of 8192 tokens. Tokens are defined in the manual as

The number of code tokens is shown at the bottom right. One program can have a maximum of 8192 tokens. Each token is a word (e.g. variable name) or operator. Pairs of brackets, and strings each count as 1 token. commas, periods, LOCALs, semi-colons, ENDs, and comments are not counted.

The specifics of how exactly this is implemented are fairly esoteric and end up quickly limiting how much you can fit in a cart, so people have come up with techniques for minimizing the token count without changing a cart’s behaviour. (Some examples in the related reading.)

But, given these limitations on what is more or less analogous to the instruction count, it would be really handy to have constant variables, and here’s why:

| -- 15 tokens (clear, expensive)

sfx_ding = 024

function on_score()

sfx(sfx_ding)

end

function on_menu()

sfx(sfx_ding)

end

|

| -- 12 tokens (unclear, cheap)

function on_score()

sfx(024)

end

function on_menu()

sfx(024)

end

|

The first excerpt is a design pattern I use all the time. You’ll probably recognize it as the simplest possible implementation of an enum, using global variables. All pico-8’s data — sprites and sounds, and even builtins like colors — are keyed to numerical IDs, not names. If you want to draw a sprite, you can put it in the 001 “slot” and then make references to sprite 001 in your code, but if you want to name the sprite you have to do it yourself, like I do here with the sfx.

Using a constant as an enumerated value is good practice; it allows us to adjust implementation details later without breaking all the code (e.g. if you move an sfx track to a new ID, you just have to change one variable to update your code) and keeps code readable. On the right-hand side you have no idea what sound 024 was supposed to map to unless you go and play the sound, or label every sfx call yourself with a comment.

But pico-8 punishes you for that. That’s technically a variable assignment with three tokens (name, assignment, value), even though it can be entirely factored out. That means you incur the 3-token overhead every time you write clearer code. There needs to be a better way to optimize variables that are known to be constant.

What constants do and why they’re efficient in C

I’m going to start by looking at how C handles constants, because C sorta has them and lua doesn’t at all. Also, because the “sorta” part in “C sorta has them” is really important, because the c language doesn’t exactly support constants, and C’s trick is how I do the same for pico-8.

In pico-8 what we’re trying to optimize here is the token count, while in C it’s the instruction count, but it’s the same principle. (Thinking out loud, a case could be made that assembly instructions are just a kind of token.) So how does C do it?

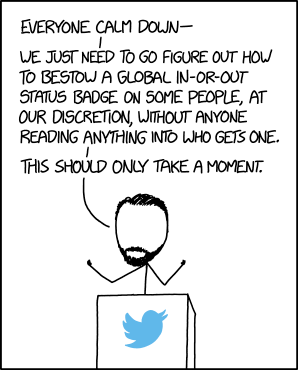

Verification on Bluesky is already perfect

Verification on Bluesky is already perfect

Lies, Damned Lies, and Subscriptions

Lies, Damned Lies, and Subscriptions

Jinja2 as a Pico-8 Preprocessor

Jinja2 as a Pico-8 Preprocessor