The following are exerpts from my fully transcribed playthrough of Psycholonials, which I wrote last summer. If you aren’t familiar with psycholonials or haven’t played the game, I recommend reading that to catch up.

If you’ve already played Psycholonials though, here’s some food for you. Exerpts though, not the whole thing.

Exerpts

On Music

The song Together was originally the score to the 2013 independent short film High Tide, which was released that same year as Someday (feat. Astro Kid). A number of other tracks from the Psycholonials EP came directly from Clark Powell’s Namesake (where Together was re-released as Day that Never Came) or from unreleased HS music team WIPs.

At about that point in the paragraph, I started writing the sentence “It’s like Clark Powell’s megalovania” but then I died of a heart attack and thus could not finish that thought.

As of the Psycholonials album release, those albums were deleted completely from Powell’s bandcamp page. Clark discussed a “cleanup” on twitter before the Psycholonials release, but has since deleted the tweet.

However, since then (approximately November 2021) Clark has re-listed his albums.

On Clowngender

So, let’s talk xenogenders. Actually, no, let’s not; I for one feel woefully underqualified to touch on that.

I will instead just point out that clowngender is apparently already a thing, and not something Andrew Hussie invented. It’s also not very much like the gender Zhen describes here. What she describes — “[ressonating less] with the entire concept of gender at all, like youre transcending the entire conventional spectrum, and seeing gender for the farcical social construct it really is” — is Agender, another thing Psycholonials did not invent.

I realize I’m being a little hard on the author here. I guess I take issue with this to the degree that the game thinks it’s inventing something new and profound, which is what I’m interpreting it as doing. If it doesn’t mean to be doing that, then that bothers me less.

Also, putting nonbinary as the dead center of the male/female axis and calling that understanding “standard” is… whew, that’s super wrong, right there. Whether it’s Zhen or the author who’s getting it wrong, I don’t know, but that ain’t it.

On the Engine

Psycholonials is written in Unity, apparently, using middleware called Naninovel. That surprises me, because so far everything seems like it could have been written in something like Ren’py or game maker. Unity seems like overkill for something as light as this, and ren’py is a solid VN engine that Andrew is already familiar with, having produced two full ren’py games already.

The various animations seem to have been originally written in flash, but they’re rendered as videos and just played as webms in-engine.

I get very distracted playing this game because the pixels are so wrong. All these scaled pixel art assets have anti-aliasing done on them, meaning the edges are at once blocky and blurry. It honestly gives me eye strain looking at it. I ended up running the game in a very small window for the LP, which helped a little.

Apparently, the actual art assets in unity are aliased, so it’s not an engine scaling issue, they were just imported wrong, in the equivalent of saving everything as a jpeg.

On Mixels

I honestly love how the art in Psycholonials plays with resolution. The mixed pixel resolution (mixels? are actually a very expressive tool. You’ll commonly see things like that last panel, where the body is low-resolution and upscaled without any filtering, and then the face is drawn on at another scale. It’s actually really charming, and it allows for things like that Percy panel, where the face is comically simplified, to work naturally within the artstyle.

On Money

zhen you idiot, you’re a billionaire. there are so many things you could be doing that aren’t this. i know I’m supposed to say this girl needs therapy but maybe therapy isn’t for you. maybe just go to prison

It’s interesting how this story revolves around this political ideology that the player knows so little directly about. It’s defined in a manifesto that was published in-universe, but which the player has not been shown.

The ideology itself seems to be “society is bad, do whatever crimes you want, I was mad anyway.” It’s almost South Park-esque in how much it romanticises applied apathy and the pursuit of… what? Money, followers? A bunch of instrumental goods that just sit in a hoard and aren’t being used for anything, good or bad. And with how willing she is to rope other people in and casually destroy their lives, it’s obvious there’s no room here for any actual respect towards others. Zhen says she has these long-term goals, but if she did she wouldn’t be taking these absurd, suicidal risks.

I don’t know if this was the intended read, or if the authors really thought they had come up with something deep and meaningful even though it’s obviously terrible if you think about it for even a minute.

I wonder if there are zhen did nothing wrong stans out there, somehow. Probably not, because this game did not sell well.

On CHAZ

So there are a lot of specific historical events from 2020 being referenced here. Obviously Covid, but also the mass protests against police brutality following the murder of George Floyd, and specifically the occupation of Seattle dubbed the Capitol Hill Autonomous Zone (CHAZ) in June. The idea, basically, was to cut off police presence in the area entirely, and show that the community could support itself and thrive without a militant police presence.

Wrapped up in the real-life discourse around protesting was this concept of “outside agitators”. This is rhetoric used to discredit political unrest by saying the actors came from “outside” — either from outside the affected community, or physically foreign agents — and the visible unrest doesn’t represent any legitimate grievances of the people.

Notably, in real life, there was actual police brutality, and the “outside agitators” narrative was a false one. There were actual atrocities being protested, instead of just people who got angry on the internet. Psycholonials has yet to directly touch on the former, other than just saying it’s the case; ascribing adjectives to it through the lens of Zhen’s narration.

Also, unlike what happened the actual capital hill autonomous zone, there is zero mutual aid or any sort of community support on Clown Island. In the absense of anything to suggest otherwise, it seems like it’s every clown for themself, with nothing resembling production, sustainability, or support. Again, just no community. It is, again, the kind of militaristic anarchy fantasy you would expect to see a villain of a story execute.

Maybe Psycholonials is a lesson in the importance of not organizing your social movement around unstable people whose primary motivations is their personal frustrations and fame. That could be a good lesson: “hey, don’t base your important social movement around Instagram influencers.” I could get behind that.

On Confused Narration

This story about systematic oppression would really, really hit better if it demonstrated the existence of any.

Really, more than anything, this is a great story about the dangers of cult mentality, although I don’t think it means to be. Like, this is a great dive into cult behaviour and some of the serious issues we’re running into today in the real political landscape about rallying behind charismatic figureheads, but I don’t think that’s what Andrew’s going for.

See, the trouble is, I want to assume that all these horrific things are meant to be bad, but given that Andrew’s friends have already just out-and-out publicly advocated for public lynchings of people they wanted to cancel online, maybe not? Based on the text so far and the context of the writing I really do think the author actually thinks they came up with a neat cult.

On Pathological Narcissism

ABBY: Keeping an unsorted list of people you’ve decided are bad is the kind of thing crazy dictators do

Z: im not planning to do a mass purge and therefore it is okay to prepare all the resources and infrastructure to do one if i decide to later

ABBY: Hm. You are still my friend, but maybe I want to engage in your cult slightly lessYou think it’s a ridiculous idea that you might go on a hater killing spree. You know you’re better than everyone in history who’ve been like you up to this point, because you’re very self-confident.

Suddenly, the person you murdered without justification’s murder is justified! It is very convenient for your present ethical dilemma. Anything you do will turn out to be justified and right, because you are so very confident, and that is what determines if a person’s actions are good or not. I, the story’s framing, am telling this to you, the reader.

ABBY: I blame myself for my parents’ murder, because I was too complicit in your murder cult. we’re still cool tho

You (zhen) think this murder is your fault, for not doing a different murder earlier.

You remember Abby’s warning about murder lists, though, from mere moments ago.

RIOTUS: Hey. Anyone who opposes you in any way is an absolute threat, and need to be killed

Z: well, i know abby is right, actually, but my new good friend riotus makes a good point about how i am perfect and everything i do is justified, so i will do those murders instead of not doing them, as was our previous plan

Zhen is, of course, a textbook narcissist, so it’s not surprising that Abby’s concerns don’t have any effect on her. Abby is there to fuel her, not to be a friend.

Joculine here is murdered for revenge, not because she did anything harmful to the organization. Zhen doesn’t even think she’s a saboteur! She’s not considered a suppressive person, she’s murdered because the leader has a personal grievance with her, and then the murder is justified after the fact.

No, really, look at that. Zhen hates Joculine because she was mean to her online in the past. Maybe she was just a troll, or she called Zhen out on some legitimately bad behaviour. That’s left deliberately unclear. And now she’s hinted that she wants a promotion. That’s what got her killed. Not killing Abby’s parents, not anything else. And that murder is portrayed as a heroic, narratively satisfying act!

Joculine is summarily judged and executed for the crime of being an anti. And I use Anti here in the same way as the story: a poorly-defined truncation that ultimately only serves to label people as with you or against you. This scene, where Zhen murders Joculine for being mean to her online, really is one of her lowest points. It’s the basest, most absurd way one could react to “cancel culture”.

So why does the framing of the story love it?

This scene gets an animation. The camera adores Zhen during the full sequence of gunplay. The moment is satisfying, and the afterglow is proud.

So does the story mean to explicitly glorify this? Yes. I don’t know any other way you could read this but yes.

On Violence

This chapter has such a fun and interesting political dialogue I really didn’t want to interrupt it. Abby’s concerned that Zhen’s plan of “just do stuff” isn’t a great one, specifically because it literally isn’t solving the problems it was meant to solve. Like, textually, we’re told that; aside from popularity, it’s failing.

Then Zhen proposes another plan that consumes resources without directly impacting anything they mean to impact. See, all Zhen is interested in is the destructive side of revolution. Again, textually:

Z: its perfectly simple

Z: yes, american imperialism is evil, so we are taking a stand against it

Z: and the only way to do that is capture and repurpose territory in order to weaken america

All Zhen’s steps are destructive. Kill a cop, kill more cops, take an island, take another island. Gain popularity, social influence, and money along the way, of course, but the real goal here is to lash out against capitalism.

Abby, of course, points out that jubilite successes are actually benefiting capitalism, and that Zhen doesn’t actually have any sort of plan to do any real damage to her target aside from lashing out at whatever edges she can reach.

Zhen’s retort to this is confidence. She’s got clout, she’s got tanks. She feels in control. What she doesn’t have is any plan that could possibly result in the “fall of America” or even any plans for how to run a country. No economic or political system in place, just hot revolutionary fervor. “Z: once weve achieved total victory, there will be PLENTY of time to sort out how to run governments and shit”. Zhen is conquest and only conquest.

On Authorial Intent

Throughout this story I’ve occasionally poked fun at the characters or poked fun at the writing. Those should be distinct and separate things, of course. In any piece of fiction, the writer and the written characters aren’t the same, and can’t be treated as synonymous. Just because someone writers a character — even the protagonist — doing something doesn’t mean they agree with that decision. This is a basic distinction, and should generally go without saying.

There are some cases, though, where that distinction can sorta break down. For psycholonials specifically, after going through the story, I’m forced to think that the author wants you to agree with Zhen. That there is an active thesis being made by the writing, and that thesis is that Zhen was right. I feel like that’s self-evident at this point, but I’m going to make the case for it anyway.

There’s a ton of evidence for this. Joculine’s whole deal, those spoons… this very ending conversation, for one. Zhen, shouting directly into the camera, “we were right about everything!!!!!!” as part of her happy ending. The story being told (not just by Zhen, but by the narrative itself) is that the movement was right, the violence was right, taking action — and taking action in the way that they did — was right. The problem wasn’t us, because we had hearts of gold and all that juicy self-confidence. No, the problem was… everybody else! The haters! The outside agitators who came in and… defended the world against you, I guess!

“All the left wing shit” isn’t wrong on its merits, it’s just that implementing it always ends in disaster firing squad murder, because this kind of social movement seems to naturally cause people to act that way. So it’s not your fault when it happens! The problem was that ego somehow got wrapped up in a movement that required someone motivated by ego in order to exist and succeed in the first place. Maybe the problem, really, was that other people choose to follow my ego cult.

That’s what Zhen thinks at the end, and that’s what the story is trying to say. There’s no subversion here, no bitterly ironic ending. We’re actually just supposed to agree with Zhen and see her as a hero prima facie.

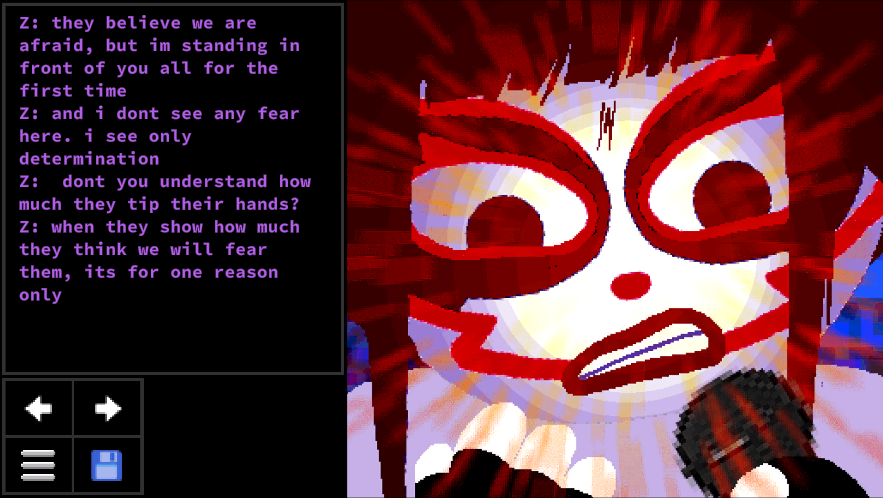

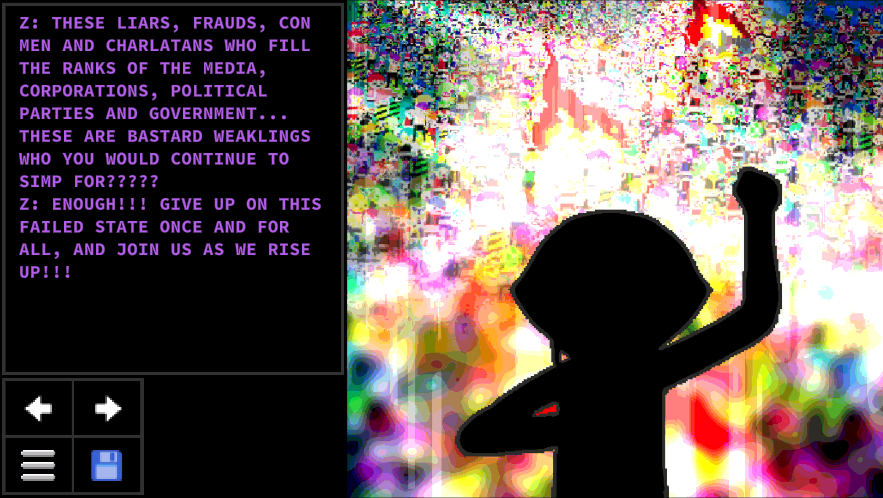

Even the camera tells that story. Look at the shots in Chapter 8:

This isn’t supposed to be a deranged rant, this is meant to be righteous anger given as the hero’s last stand. The camera is on her side throughout.

If I were wrong about that — if this whole story was all an elaborate exercise in subverting the idea that Zhen is a hero — I would expect to see a few things that I just don’t. Fundamentally, I’d expect to see anything Zhen does portrayed by the storyteller as potentially a bad thing. There’s none of this. There aren’t any consequences, obviously, but there’s also a conspicuous lack of narrative or artistic choices to even hint to the reader that something might be wrong. If you want to question Zhen at any point in the story, that work is left entirely up to you to do for yourself.

There’s just a lot of post-hoc justification in this story. I talked about Joculine already, and she’s probably the strongest example of it.

There’s also a lot of cases where the tone becomes negative after something awful happens, but never because of the awful thing. The tone shift feels almost obligatory. It turns out it was good to kill Joculine, not because she had people killed, but because she was mean to us online once. It was bad to issue a sweeping kill order not because murder is wrong, but because it made our friend Abby uncomfortable. Et cetera.

And, I mean, that’s just looking at the narrative on its own without any real-world evidence. That’s because if you add in even a little bit (shoot there’s too many for the gag) of context about the ideas Andrew Hussie promoted IRL, that seals the deal pretty overwhelmingly. So leading with that would be cheating.

On Cancel Culture

So, believe it or not, a lot of what Zhen says here about cancel culture is actually right, taken literally. It’s absolutely possible to pick out a goal (“hurt a person I dislike”, for instance) and then use a phony excuse to go about doing it. Want to hate women in the games industry? Hate women in the games industry, but insist it’s about ethics in journalism somehow. Really mad that trans people exist? Make a forum where you make threads about specific public trans people so you can catalogue every individual stupid thing they do, but insist their identities aren’t the reason. Want to harass someone you don’t like over some personal squabble from when you were fourteen? Put together a callout post and publish a bunch of weird old blackmail material. Sometimes it’s vindictive, sometimes it’s out of a misguided sense of puritanianism, sometimes it really is just to get attention. It’s totally possible to use social media to pursue your own goal while using some insincere pretext you can insist is your real motivation.

The problem, of course, is that doesn’t make the reverse true. Not all concerns about ethics are fake, not all concerns about people in a community are attempts at character assassination. This is obvious, of course. The reason those cover stories work at all is because ethics or pedophilia or toxic behaviour or whatever is because those things are actually real concerns.

Now, why do I even bring that up? It’s not like people are going around saying all concerns raised about them on the internet are automatically harassment, or transphobia, or stalking, right? That would be absurd. But it happens. You see people throw on another “layer of bullshit”, as Zhen calls it, and say that all criticism of them is automatically in such bad-faith that their critics should be reviled, without any consideration of the issue itself.

You’ll see snakes call things “hit pieces” that aren’t, or people hunting down critics of anyone in their demographic just to publicly insult them. You see people say any criticism of them is an attack on whatever minority group they decide to identify with, and that their critics need to be silenced by any needs necessary. They’ll even advocate actual murder (which Zhen actually does in this story, and is praised for)! It’s all just another trumped-up pretext, but this time, instead of just hurting someone you shouldn’t, it’s a pretext that can defend even the indefensible. And, of course, there are always people who will take full advantage of being able to do the indefensible without consequence. And that’s before we even touch on how all this gets used for lateral violence in and between vulnerable communities. But I’m commenting here, not writing an essay.

I think one of the problems really is social media, actually. There’s something about social media — the rapid-fire of information, the gamification of human interaction, the platforms aiming to drive up engagement for corporate profit — that discourages people from taking the time to “penetrate the layers of bullshit” and actually think about the things being said. It’s far, far easier to just agree with whatever rhetoric the people you like already are using than to take the time and make the effort to actually look at the substance of any given issue for yourself. “Anyone opposed to X party is bad” and “anyone who even tolerates anyone I say is bad is also bad” are patently absurd evaluation metrics, but they’re sadly much easier metrics to use than thoughtfully engaging in each issue you care about. That takes real time and energy, so your social media content/effort output ratio is going to be much better if you take the shortcuts.

fandom

fandom