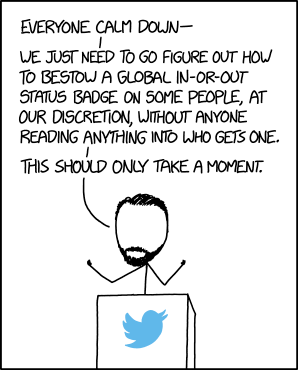

The “blue check” — a silly colloquialism for an icon that’s not actually blue for the at least 50% of users using dark mode — has become a core aspect of the Twitter experience. It’s caught on other places too; YouTube and Twitch have both borrowed elements from it. It seems like it should be simple. It’s a binary badge; some users have it and others don’t. And the users who have it are designated as… something.

In reality the whole system is massively confused. The first problem is that “something”: it’s fundamentally unclear what the significance of verification is. What does it mean? What are the criteria for getting it? It’s totally opaque who actually makes the decision and what that process looks like. And what does “the algorithm” think about it; what effects does it actually have on your account’s discoverability?

This mess is due to a number of fundamental issues, but the biggest one is Twitter’s overloading the symbol with many conflicting meanings, resulting in a complete failure to convey anything useful.

History of twitter verification

Twitter first introduced verification in 2009, when baseball man Tony La Russa sued Twitter for letting someone set up a parody account using his name. It was a frivolous lawsuit by a frivolous man who has since decided he’s happy using Twitter to market himself, but Twitter used the attention to announce their own approach to combating impersonation on Twitter: verified accounts.

In their post, they announced about a limited beta where Twitter employees would manually verify “public officials, public agencies, famous artists, athletes, and other well known individuals at risk of impersonation.” They clarify that, of course, “this doesn’t mean accounts without a verification seal are fake” and that “another way to determine authenticity is to check the official web site of the person for a link back to their Twitter account.”

At this point in time, the process is clearly focused on impersonation. Verification is to help prevent confusion. But already there’s a sneaky conflict buried in the process: it’s a beta, and they’re starting with individuals who are well known, so already there’s some doubt introduced as to the meaning of verification. Does it mean you’re who you claim to be, or that you’re both that and somehow noteworthy? And who defines that?

Twitter verification remained a closed don’t-call-us-we’ll-call-you process until 2016, when Twitter deigned to let people humbly request that Twitter verify them. Even with open admissions though, it’s still a “private club, gated behind an invisible, exclusionary admissions process that wasn’t documented anywhere.” But even this announcement came with more language about what verification means, which is again problematic:

Verified accounts on Twitter allow people to identify key individuals and organizations on Twitter as authentic, and are denoted by a blue badge icon. An account may be verified if it is determined to be of public interest. Typically this includes accounts maintained by public figures and organizations in music, TV, film, fashion, government, politics, religion, journalism, media, sports, business, and other key interest areas. … We took a look back and found that the @CDCGov was one of the first Twitter accounts to be verified, in an effort to help citizens find authentic and accurate public health information straight from the source.

Ignoring the awkward sentence construction at the top, let’s identify the various conflicting goals here: “authentic” again supports this idea of verification as a defence against impersonation, but then “key individuals … determined to be of public interest” again reinforces this idea of verification being a kind of endorsement given to people an elite committee at Twitter deem to be good and important. They even give “be like the CDC” as an implied example of what it means to be noteworthy. What are people supposed to make of that?

Remember the original announcement, where Twitter mentioned that “another way to determine authenticity is to check the official web site of the person for a link back to their Twitter account”? As Anil Dash pointed out in What it’s like being verified on Twitter, Twitter already has a way to verify the authenticity of a Twitter account for analytics: authoritatively linking it to a website. In other words, you could have a badge that confirms “this is the real twitter account of giovanh.com” by just using the existing analytics logic, which would add a layer of trust and identity on top of Twitter’s existing username system. (In fact, this is the basic system Mastodon uses.)

Why not use a system like this to verify identities once they opened up the process to the public, instead of still requiring a committee to verify people? Because it was already too late to just verify people’s identities. After day 1, it wasn’t just about impersonation anymore. By this point they had overloaded the “blue check” signifier too much already, and couldn’t let “just anybody” be verified.

All the different things the blue check can mean

The big problem is that the blue check symbol is wildly overloaded. Verification tries to simultaneously do many different things and therefore fails at all of them because those goals are not aligned with each other. Verification is generally a layer of “trust”, but what exactly is that trust supposed to be in?

Thu Aug 19 21:32:25 +0000 2021On Wednesday, @DannyDevito expressed solidarity with striking Nabisco workers.

“NO CONTRACTS NO SNACKS,” he tweeted.

Today, Twitter stripped him of his verified status, DeVito confirmed to More Perfect Union.

Thu Aug 19 22:39:18 +0000 2021The utter failure of the blue checkmark is Twitter's complete inability to decide what it means and communicate that to people. "This is really who they say they are" is such a home-run concept, but it got loaded with so much baggage that we're... here. twitter.com/MorePerfectUS/…

Replying to giovan_h:Sat Nov 18 01:44:26 +0000 2017If you simplify twitter's verification policy by removing all the contradictory parts, all you get is "It's blue"

Twitter Verification requirements - how to get the blue check reads

The blue Verified badge on Twitter lets people know that an account of public interest is authentic. To receive the blue badge, your account must be authentic, notable, and active.

Verification as authenticity

That first point is what it’s “supposed to” mean: “authentic”. That, when you see a user with a name and picture and bio, and you immediately have an idea of who that person is claiming to be, you can look for the checkmark to confirm that you’re right.

This is already a deeply flawed concept. In order for Twitter to craft a metric that meets that criteria, they have to know who people will think an account is supposed to be, which is of course impossible because that assumption people will make is determined by a function of both the account and the person reading it, not just the account itself. But, just for the sake of argument, let’s pretend it’s possible to get this right, and not get too down in the weeds of the various bad policies refining this is going to produce. But even so, let’s take “verification as authenticity” and run with it.

This super-duper failed.

Twitter is a company willing to use their primary verified safety account that alerts users about breaches and major security incidents to do branded content for DC comics. It shouldn’t be a huge surprise that they couldn’t resist tacking on meanings and connotation to the verified mark either.

In a sense, this is a classic linguistic descriptive/proscriptive problem. Does the symbol mean what you say it means, or does it mean what people understand it to mean? This is made worse by the obvious convergent instrumentality at play here.

Verification as authentication failed to such a degree that in 2018, they hard-coded “automatically suspend anyone who sets their display name to Elon Musk” into their system to block spam accounts, because the blue check was completely worthless at doing its job.

Sun Jul 29 01:12:27 +0000 2018elon musk scam account thoughts:

1. this is the actual problem that twitter verification is supposed to solve

2. twitter literally just hardcoded "Elon musk" into their system and called it a day

And that’s hardly the only case like that. Twitter has a “government official” flag that seems entirely orthogonal to its existing verification system, even though ostensibly they’re supposed to be doing the same thing: verifying that this account really is “the official voice of the state”. That’s… that’s “verifying” the identity of the account, right? Except verification can’t be used for that, because it’s already been run into the ground by all the other concepts Twitter couldn’t resist tacking onto it, like

Endorsement

Sat Nov 18 01:43:02 +0000 2017Twittee: people are confusing verification with endorsement. It's totally not endorsement, you guys

Also Twitter: we added a morals clause that includes your behavior on other websites

From that same “how to get the blue check” page,

Verification is currently used to establish authenticity of identities on Twitter. The verified badge helps users discover high-quality sources of information and trust that a legitimate source is authoring the account’s Tweets.

So it’s for “high-quality sources of information”. Talk about a load-bearing phrase, they really just drop that and leave. It’s no wonder that people feel like the checkmark signals that it conveys credibility to the source, Twitter literally says that it does. What happens when quality and legitimacy come into conflict?

That’s not a hypothetical. In 2017, Twitter had to pause their verification process entirely after they verified violent neonazi Jason Kessler’s Twitter account.

Thu Nov 09 16:03:49 +0000 2017Verification was meant to authenticate identity & voice but it is interpreted as an endorsement or an indicator of importance. We recognize that we have created this confusion and need to resolve it. We have paused all general verifications while we work and will report back soon

Replying to TwitterSupport:Wed Nov 15 22:30:58 +0000 20172 / Verification has long been perceived as an endorsement. We gave verified accounts visual prominence on the service which deepened this perception. We should have addressed this earlier but did not prioritize the work as we should have.

At first blush this seems unfair, because verification was supposed to be about authenticity, not an endorsement. And the verified account really was the Twitter account of the real Jason Kessler. But at this point that ship had long sailed already. People were outraged because by this point verification was de-facto endorsement, despite Twitter’s claims otherwise. That’s why they refused to verify Julian Assange’s account.

By this point the company understood there was a dual purpose: The little blue tick is both a way to verify people are who they say they are and also convey to users who is a trustworthy source of information.

If you’re browsing Twitter and you see a tweet from someone you don’t recognize, you might not know at first whether you trust the source to be providing reliable information. Then, when you see the tick next to their name, you know that Twitter is endorsing this person as a trustworthy source, and so they’re probably telling the truth that Jews control the media. Because Twitter has become a major news platform, this matters a lot.

To make matters worse, this verification/endorsement happened less than a month after Jack Dorsey promised more aggressive enforcement against hate groups. To verify Jason in this environment was utterly tone-deaf, and ultimately representative of much deeper issues within the verification process. As Jack confirmed:

Thu Nov 09 16:20:17 +0000 2017We should’ve communicated faster on this (yesterday): our agents have been following our verification policy correctly, but we realized some time ago the system is broken and needs to be reconsidered. And we failed by not doing anything about it. Working now to fix faster. twitter.com/twittersupport…

So, officially, the internal verification policy still said Jason qualified for verification, even though the public-facing messaging — even the official messaging! — said the symbol indicated a high-quality, reliable source of information.

Mon Dec 12 21:46:09 +0000 2016Twitter verifies white supremacists because they wrongly believe verification is an internal corporate process, not a signifier in culture.

Replying to anildash:Mon Dec 12 21:47:53 +0000 2016This is a classic tech company error — we exist in society, and we don’t get to define our place in society by fiat. The community does.

You’ll still frequently find cases like Kessler’s, where people complain that Twitter’s verification system is being used to platform unconscionable content:

Tue Nov 16 23:39:52 +0000 2021Fake reporter Jack “Fmr CBS News” Posobiec is once again using the platform @verified gave him to spread lies — this time about Rittenhouse jury:

Sat Mar 26 19:28:03 +0000 2022THREAD: The problem with @Twitter and its indiscriminate @verified system, which allows disinformation agents not just to exploit the platform, but to actually thrive on it. This operator linked to the Iranian and Russian propaganda machinery got nearly 40K retweets for this.

Is this fair? Maybe not, in the imaginary world of 2009, where verification is a moderation tool to prevent impersonation. But in the real world, where verification is a very real and tangible endorsement, it really is a problem if Twitter is allowing this endorsement to spread where it shouldn’t. It creates responsibility for them, but at this point that’s just the check they wrote for themselves.

It means you’re a high-quality, elite person

More than just endorsement though, there’s a natural conflation between “important” and “good”. This is where we start seeing verification used as a status symbol, with verified accounts seen as somehow “elite” as a higher binary tier of users.

Mon Oct 31 01:28:43 +0000 2022The point of Twitter verification is that for certain individuals/organizations it’s useful to be able to verify their statements are coming from them. (This is why so many journalists/reporters are verified.) It’s supposed to help combat disinformation, not be a status symbol.

Replying to AstroKatie:Mon Oct 31 01:28:44 +0000 2022People think of it as a status thing because a lot of people with status are verified but the causality is that if you’re well known, you’re more likely to be a target for impersonation and/or there’s more public interest in being able to verify that your statements are yours.

Especially among less tech-savvy Twitter consumers, the verified badge is seen as a status symbol, rather than the arbitrary Twitter-defined signifier it is. That’s why Twitter tried to make it clear they didn’t want it to mean status from the outset, because they recognized the danger in correlation. But they didn’t do enough to prevent it.

Anil Dash discusses in Verifiably True (2021):

Unsurprisingly, as with anything that’s perceived to convey status, verification is one of the parts of Twitter that most consistently inspires resentment, anger, or frustration with the platform.

…

No surprise, then, that this leads to some measure of conspiracy theories and magical thinking. Regular people outside of the media bubble have developed an entire set of folk beliefs around what verification means, based on what they tell me about why they want to be verified. There are intimations about doing better in Twitter’s algorithm, of course — an entirely reasonable assumption. But there’s also this broader sense that it opens up a world of possibilities. More than one guy has DMed me saying he needs to be verified because he’s about to drop his mixtape, and he wants to make sure people hear it. There’s a missing step between a few blue pixels and millions of ears that I don’t quite have a grasp on, but I can certainly understand the emotional drive behind it.

Twitter is full of little hierarchies: follower counts, likes, retweets, networks. But there’s one big stratified social split, and that’s verification. It feels like if you can get that badge, you’ve made it. You’re a big shot.

Power tools and advertisement bonuses, for some reason

Having a verified account literally gives Secret Privileges to special users. There are special filters only verified Twitter users have access to (despite these being useful functionality for non-verified users too). These are useful for power-users, but also really valuable tools for companies and advertisers wanting to engage more constructively with the public. And they just don’t have access to those features unless they convince Twitter that they’re very special boys.

Verified users also tend to be prioritized (by both Twitter’s algorithm and things like external searches) because of the correlation between verification and quality. This adds additional baggage to what “verification means”, though, as anything that directly affects visibility is going to be prized for its effects alone, regardless of whatever else it’s meant to signify.

Economic necessity: it means you can pay your bills

It’s fun to talk about people feeling like being verified will solve their problems, and point out how there’s magical thinking around the signifier, but in a way that’s not totally untrue.

In the internet creator economy, your online social status is, in a very real sense, your livelihood. That’s why there’s sometimes this intense desperation around verification, why people will be so excited and — really — relieved to get it, because it opens very real doors in their professional lives.

Again, from Verifiably True:

But there’s a broader sense that people’s attention, and careers, and opportunities, and even to some degree their lives, are mediated by platforms that are enormously powerful while being fundamentally opaque. Abstractions like “the algorithm” are unknowable, and have millions of people grinding away at a thankless video game that is not only impossible to win, but will actively adapt to keep you from winning if you get too good at it.

And then, amidst that stress and anxiety and uncertainty, there’s a signifier of status. Even better, it’s a signifier that’s tied to the promise of algorithmic privilege. People will take you more seriously, platforms will amplify your voice, and maybe this entire ecosystem will tilt more fairly in your favor.

And that last bit hits at it, I think. People are conscious of how their lives are governed by these giant, opaque, unimaginable systems. Conservatives invent conspiracy theories about censorship because they rightly feel that their lives are unfairly governed by these platforms that are stacked against the user. People are desperate for privilege because of the suffering of being trapped in an economic system that harms those without it.

There’s a very deep dive into this concept found in Hearn, A. (2017). Verified: Self-presentation, identity management, and selfhood in the age of big data. Popular Communication, 15(2), 62–77. https://doi.org/10.1080/15405702.2016.1269909, which I’ll summarize briefly here:

This new digital “affective” capitalism purloins our desires, emotions, and forms of expressivity and turns them into commodities and assets. Affective capitalism is, quite literally, run on the fuel of individual feeling and self-expression taking place online; self presentation is now a crucial part of the economic infrastructure

“Affective capitalism”, where capitalism begins intervening in intimate, domestic relationships, creates a framework where creating ways for people to express themselves — and, in this case, show their legitimacy — can be turned into an exploitable asset, if you control the systems through which that expression happens.

The verb “verify” generally means to “confirm,” “support,” or “substantiate” the truth or authenticity of some event, thing, or person. In rare instances of usage, however, “verify” can also mean “to ‘cause’ to appear truthful or authentic” (“Verify,” 2002). Following from these definitions, two inflections of the term “verified” are considered here. The first understands verification as an affirmative authentication and approval of identity around which users’ desires and affective investments circulate. The second inflection positions verification as a disciplinary mode of regulation enacted by a private or state institution that claims authorization over legible and/or “authentic” forms of identity but that, in effect, “causes” legitimate forms of identity to appear.

…

When users are contacted for verification, they are told they are three quick steps away from earning their verification badge. The site then takes them through a short quiz predicated on helping them learn “how to tweet effectively.” The lessons include learning how to double follower rates by live tweeting events, engaging more followers by asking them questions and inviting them to a live question-and-answer period, and increasing likes, retweets, and favorites by including visuals and photos. Finally, Twitter encourages the user to like and follow other verified accounts in order to increase their own “truthworthiness.”

…

The exhortations to learn how to “tweet effectively” in order to receive verification, however, clearly expose the promotional, self-serving logics of Twitter itself. In reality, the verification process works to instantiate a new kind of social sorting, or social class, predicated entirely on a form of “reputation” that Twitter itself defines, attributes, and then validates in an opaque, unaccountable manner. In this way, Twitter installs itself as a powerful arbiter of social status and value in a promotional culture and a “gig economy” where influence and high visibility are increasingly central to job stability and monetary success. As it comes to challenge more traditional forms of identity authorization, such as passports or medical certificates, however, it must be noted that the checkmark is far from an innocent indicator of a user’s “actual” identity or influence; rather, it is a careful construction with an entirely instrumental purpose.

…

The message to those who seek out and attain the verification checkmark is clear: Build an effective self-brand, cultivate a following and a reputation, and, most importantly, always be communicating. Here, individuals “are cast as quasi-automatic relays of a ceaseless information flow”, or figured as mere data outputs working to ensure “the often serendipitous reunion of commodities and money”. The grease behind this constant data generation is provided by free-lunch inducements like the Twitter verification checkmark, whose promise of social status and high visibility encourages users to perpetually work at posting and crafting themselves online. Under current volatile economic conditions, however, this kind of attention seeking and identity building is no longer voluntary so much as it is “enforced—a survival discipline for disinvested populations”

It means you’re paying them money?

And all that brings me to the last few hours, where Twitter — now headed by known fraud Elon Musk — is looking to reform the verification process by just charging for it instead.

The directive is to change Twitter Blue, the company’s optional, $4.99 a month subscription that unlocks additional features, into a more expensive subscription that also verifies users

This was originally reported as $20/mo, but Elon Musk looked at rolling that back to $8, after someone on the internet hurt his feelings.

Mon Oct 31 11:23:37 +0000 2022$20 a month to keep my blue check? Fuck that, they should pay me. If that gets instituted, I’m gone like Enron.

Replying to StephenKing:Tue Nov 01 05:16:09 +0000 2022@StephenKing We need to pay the bills somehow! Twitter cannot rely entirely on advertisers. How about $8?

Replying to elonmusk:Tue Nov 01 05:25:00 +0000 2022@StephenKing I will explain the rationale in longer form before this is implemented. It is the only way to defeat the bots & trolls.

Based on some disjointed ramblings from Elon Musk, which I guess is what counts as public relations in a full on kleptocracy, the “new vision” for verification looks something like this:

Tue Nov 01 17:36:48 +0000 2022Twitter’s current lords & peasants system for who has or doesn’t have a blue checkmark is bullshit.

Power to the people! Blue for $8/month.

Replying to elonmusk:Tue Nov 01 17:38:18 +0000 2022Price adjusted by country proportionate to purchasing power parity

Of all the even semi-reasonable ways to reform the verification system, this is not one of them.

So, Elon sees the existing system as an unfair dichotomy which creates an oppressive class system of elites. His solution to this is to… charge money for a previously free platform feature. So now, instead of verification protecting users from being fooled by impersonation accounts, or telling them what sources of information are reputable, verification would mean you have the disposable income to pay for a social signifier.

Replying to elonmusk:Tue Nov 01 17:41:23 +0000 2022You will also get:

- Priority in replies, mentions & search, which is essential to defeat spam/scam

- Ability to post long video & audio

- Half as many ads

Replying to elonmusk:Tue Nov 01 17:43:37 +0000 2022And paywall bypass for publishers willing to work with us

Oh, sorry, it also means you’re elevated to a higher social class with a vastly amplified voice in the public square, along with other special powers and privileges compared to the unverified plebeians. This… ends the oppressive class system and solves democracy, somehow?

Replying to saylor:Tue Nov 01 18:31:29 +0000 2022@saylor Yes, this will destroy the bots. If a paid Blue account engages in spam/scam, that account will be suspended.

Essentially, this raises the cost of crime on Twitter by several orders of magnitude.

Oh, also, that bit about bots isn’t a real concern of his, that’s just a lie he told to try to get out of a bad deal after failing to manipulate the market. But, if this did succeed in eliminating bots, it only do so because it required people to pay to effectively use twitter. In other words, it could only do so because it also eliminated vast swaths of legitimate voices that didn’t choose to pay Elon for the privilege of having a voice on the internet.

Replying to mmasnick:Tue Nov 01 22:41:35 +0000 2022The whole "priority in replies, mentions" bit is that while he CLAIMS he's giving "power to the people" and removing the classist system, he's actually just making it worse. Those who pay get a cleaned up Twitter. Those who don't get flooded with spam.

So what happens when you take a signifier you overloaded to mean “good, reputable, high-quality person” and start charging for it?

Well, it definitely loses the original meaning of authentication. It doesn’t mean you’re really that person, just that you have money. It also loses any signifier of being a high-quality source, if you can just pay for it.

It might cause people to pay for the status symbol, or else stop caring about it.

It will probably force independent journalists and other reputable, high-quality sources of information out of the designated “reliable” sphere, in favour of low-quality fake news sources that have the funding to pay to amplify their lies and propaganda. It’ll make twitter a more difficult place for everyone to figure out what’s reliable and what isn’t.

It’s certainly a step in the exact opposite direction of being a free-speech public square, but it’s not particularly surprising that Musk was lying about that.

Verification in my remark comments

I think the verification design pattern can be a good one. I use it myself, in my blog comments.

My account is verified, so people can’t impersonate me. That’s important. I want to be able to post comments authoritatively, without opening up the door for impersonation. Also, if someone relevant to an article showed up to say something I’d verify them so it’s clear they aren’t impersonating them.

There’s definitely value in verification as a design pattern if executed correctly, but how difficult that execution is depends on all the different problems you’re trying to use it to solve. (If it’s more than one, you’ve failed right out of the gate.)

I think this is another instance where the benefits of scoped rather than universal moderation shine. I don’t have to make a decision for the whole internet, just this space. But that’s a whole other can of worms.

Related Reading

- Nitasha Tiku, “Twitter’s Authentication Policy Is a Verified Mess”, 2017

- Content Moderation Case Study: Twitter Removes 'Verified' Badge In Response To Policy Violations (2017) | Techdirt

- Dan Phiffer, “How We Verified Ourselves on Mastodon — and How You Can Too”

- Geoffrey A. Fowler, “Twitter said it fixed ‘verification.’ So I impersonated a senator (again)”

- Sara Fischer Rebecca Falconer, “Verified” becomes a badge of dishonor (2023)

- Matt Blinder, “Dril and other Twitter power users begin campaign to ‘Block the Blue’ paid checkmarks” (April 2023)

fine, I’ll separate out the Elon Musk stuff

- Matthew Sheffield, “Elon Musk is humiliating himself and all we can do is watch in horror”

- Mike Masnick, “Hey Elon: Let Me Help You Speed Run The Content Moderation Learning Curve”

- Paris Marx, “Elon Musk's Flawed Vision and the Dangers of Trusting Billionaires”

- Elon Musk, Under Financial Pressure, Pushes to Make Money From Twitter

- Nilay Patel, “Welcome to Hell, Elon”

- John Bull on the “Trust Thermocline” (thread)

- Bak-Coleman, J. B. et al, E. U. (2021). Stewardship of global collective behavior. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 118(27).

- Justin Jackson, “Is Twitter Done?”

- Why Is This Happening? The Chris Hayes Podcast, “Twitter’s Elon Musk Era with Kara Swisher”

- Ed Zitron, “The Fradulent King”

- Christia Peterson, “twitter blue screenshot storyline”

Replying to ZenOfDesign:Fri Apr 21 21:26:05 +0000 2023The ironic thing is that charging for verification would be VERY good for Twitter. If Twitter charged a ONE-TIME fee of $20 bucks, and spent that money actually verifying that people were who they said they were, a ton of people would likely sign up for that.

12/

cyber

cyber