Hear me out: copyright is good.

When it comes to copyright it can be very easy to lose the forest for the trees. That’s why I want to start this series with a bit of a reset, and establish a baseline understanding of copyright doctrine as a whole, and the context in which our modern experience of copyright sits.

The current state of copyright law is a quagmire, due not just to laws but also international treaty agreements and rulings from judges who don’t understand the topic and who even actively disagree with each other.

That convolution is exactly why I don’t want to get lost in those twists and turns for this, and instead want to start with the base principles we’ve lost along the way.

You don’t need to understand the layers to see the problem. In fact, intellectual property is a system whose convolutions hide the obviousness of the problem.

Complexity is good only when complexity is needed to ensure the correctness of the outcome. But here, far from being necessary to keep things working right, the complexity hides that the outcome is wrong.

But that outcome, our current regime that we know as copyright policy, is so wrong — not only objectively bad, but wrong even according to its own definition — that at this point it takes significant work just to get back to the idea that

Copyright is supposed to be good

This is my controversial stance, and the premise of my series: copyright (as properly defined) is a cohesive system, and, when executed properly, is actually good for everyone.

At this point, you might think I’m setting myself up to fail the purpose of a system is what it does test.

If there’s some definition of what copyright “should” be, but it doesn’t map to the system of copyright as it actually exists, why bother spending time with a definition we fully expect not to apply to the system?

I’m not trying to imply that our current system is justified by a definition that’s meant to be its “purpose” even while the definition fails to describe how the system really works. In fact, I ultimately want to do the opposite.

The word “copyright” can refer to two very different entities.

One is copyright as a system of political power. This is the overall system, composed copyright legislation, international treaties, and systems of enforcement.

The other is copyright as a philosophical doctrine. This is the basis (at least ostensibly) for copyright law and enforcement power, and what the system is meant to derive from.

Copyright as a political system should be an implementation of this philosophy, and its power derives its legitimacy from how well it maps to the philosophy and correctly implements it goals.

The philosophy should be good for artists, but the reality of the power structures is bad for artists.

Not only is that bad, it also makes the discourse around the topic insufferable, because people talking about “copyright” usually aren’t referring to the same thing!

I argue that the philosophical doctrine of copyright is actually remarkably sound; the goals work, but the system of power has gone rotten.

What’s more, we can identify the ways it’s gone bad by comparing it to the philosophy that it should derive from, and find that instead of being an implementation of the philosophy, it’s been corrupted, and ends up pushing a completely contrary set of goals.

What we’re subjected to today in the name of copyright does not come from the real principles of copyright. Compared to the current state of US intellectual property law, the “real copyright” I’m talking about is like grass so utterly smothered by concrete that not only do no strands poke through, everyone involved has forgotten it was ever there.

The situation is so bad that even though I think copyright should be a good thing, I think our current bastardization of it may be worse than nothing at all, to the point where we’d be better off with the problems real copyright is meant to solve than with all the new, worse problems it’s inflicted on us.

But because what we’re enduring now is a corruption of another thing and not its own original evil, we’re not limited to measuring it by the harm it inflicts: we can also measure it by its deviation from what we know it should be.

So what’s the good version? This true, unadulterated form of creative rights?

The Freedom Motif

The Freedom Motif

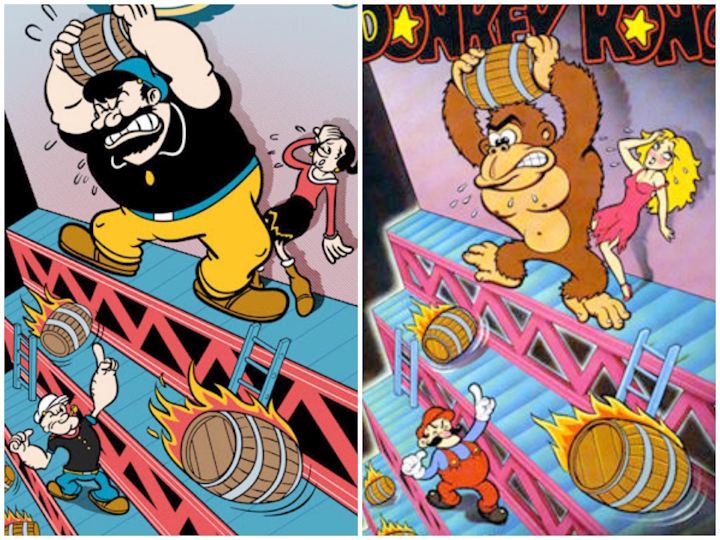

Copyright abusers lost their claim

Copyright abusers lost their claim

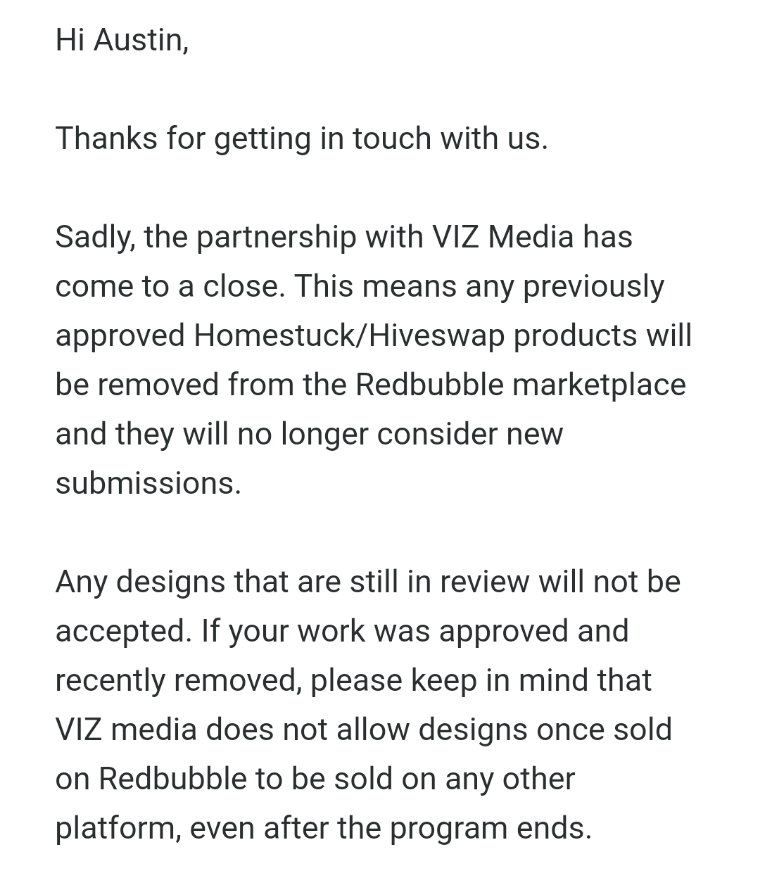

Notes on the VRC Creator Economy

Notes on the VRC Creator Economy

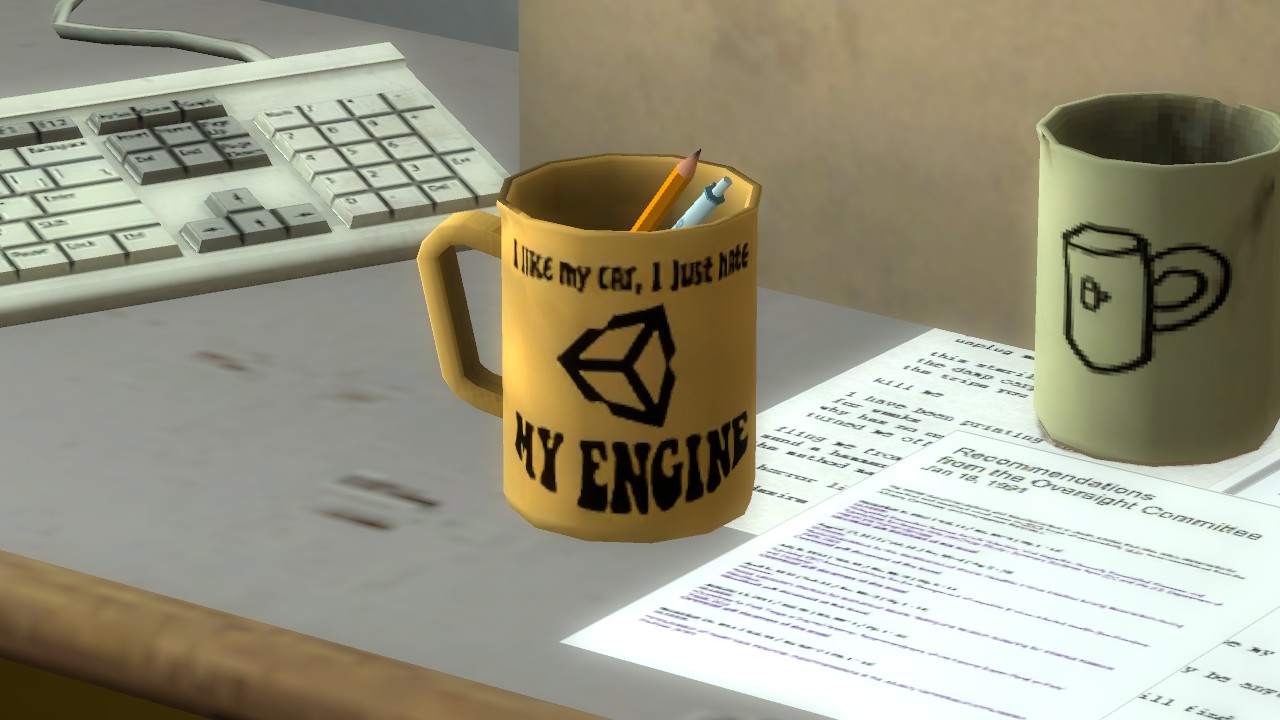

“I love my car, I just hate my engine”

“I love my car, I just hate my engine”